The beginnings

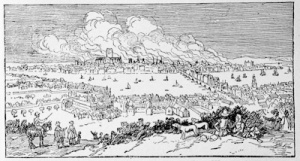

On the night of September 2, 1666, a small fire broke out in the premises of a baker's shop in Pudding Lane, London, perhaps started by the carelessness of a maid.

If it was carelessness, it was carelessness that had enormous and disastrous consequences, for the fire spread and soon the whole building was alight. In the close-packed streets of London, where buildings jostled each other for space, the blaze soon became an inferno. Fanned by an east wind, the fire spread with terrifying speed, feeding on the tar and pitch commonly used to seal houses.

Pepys' View

Our best account of the Fire comes from the diaries of Samuel Pepys, Secretary of the Admiralty. He watched the course of the destruction from a safe position across the Thames, and called it, "a most malicious bloody flame, as one entire arch of fire... of above a mile long. It made me weep to see it. The churches, houses, and all on fire and flaming at once, and a horrid noise the flames made, and the cracking of houses at their ruin ... Over the Thames with one's face in the wind you were almost burned with a shower of firedrops." Pepys buried his wine and parmesan cheese to keep those valuable items safe from the flames.

Counting the cost

After four days while helpless citizens stood by and watched the destruction of their homes, the wind mercifully died and the fire was stopped. Then the accounting took place.

When a dazed populace took stock of the damage, they must have wondered if Armageddon had come. Fully 80% of the city was destroyed, including over 13,000 houses, 89 churches and 52 Company (Guild) Halls. The spiritual hub of the city, Old St. Paul's Cathedral, was nothing but rubble. It was a disaster of unprecedented proportions.

Wren's opportunity

Well, one person's disaster is another person's opportunity. Within days of the fire's end, Christopher Wren submitted plans to Charles II for the complete rebuilding of the city. Wren's grand scheme called for cutting wide avenues through the former warren of alleys and byways that had made up old London, opening up the city to light and air as it were.

Charles liked the scheme, but he realized that the expense and the necessity of rebuilding as fast as possible made it unworkable. Instead, he appointed Wren to rebuild the city's churches, including St. Paul's, a position the young architect filled brilliantly over the next fifty years.

The Monument

Wren also was responsible for building the London Monument (1671-79), a memorial commemorating the fire. The Monument (on Monument Street, naturally!) is a slender column 202 feet high, which is the exact distance from its base to the site of the baker's shop where the fire began.

The original plans for the Monument called for a statue of Charles II on top, but Charles objected to the honour, fearing that the people of London would then associate him with the disaster. Wren replaced the statue with a simple bowl with flames emerging. The Monument is open year-round and can be climbed to gain a wonderful view of the city. At the base is a carved stone relief depicting the story of the fire.

One final note on the Great Fire. In 1986 the Baker's Company issued a somewhat belated apology for the fire (320 years late). Well, better late than never.

Related:

The Plague

Christopher Wren

To see:

London Monument

Golden Boy of Pye Corner

- an unusual gilded monument marking the furthest extent of the flames

Not to mention dozens of Wren churches around the city! The most famous is St Paul's Cathedral, but you could easily fill an entire day or more visiting Wren churches in the city

Also see "Stuart London" in our "London History" guide.