When King Alfred died England south of the Tyne was divided into two parts, the line passing diagonally from Chester to the Thames estuary below London. Alfred's treaty with the Danes had simply recognised the facts.

Where the Danes were already masters they were allowed to remain masters; the king had better work to do in organising his half of the country than in embarking upon an impracticable attempt to reconquer the Danelagh. For it must be borne in mind that the north and east had never owned the overlordship of Wessex till forty years before Alfred's accession.

In East Anglia the Saxon dynasty had no stronghold, and the last sub-king, St. Edmund, had apparently been chosen by the men of East Anglia from the old line, not appointed by the king of Wessex from Ecgbert's line. The Angles might not love the Danes, but after all the Danes were little more alien than the Wessex folk.

Finally, if there was any sort of submission of the Danelagh to Alfred's sovereignty it was of a merely formal character. The "Frith" or agreement with Guthrum manifestly aimed at discouraging intercourse between the Saxon kingdom and the Danelagh, probably because such intercourse was regarded as more likely to bring about hostilities than to increase amity.

Edward the Elder

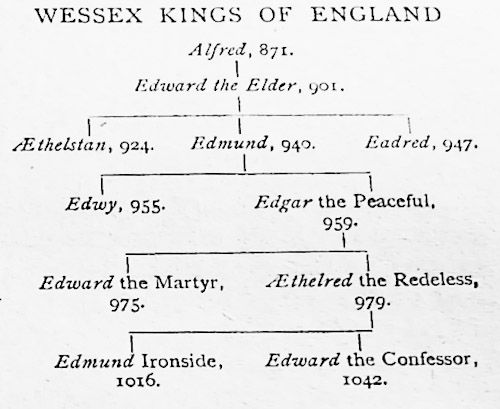

Alfred's own kingdom included a large part of Mercia and was under the government of an ealdorman, AEthelred, who may have belonged to the house of Offa, and who had to wife Alfred's very remarkable daughter AEthelflaed, who, after her husband's death, was known as the Lady of Mercia. Alfred's successor on the throne of Wessex was Edward, called the Elder. The relations between Wessex and the Danelagh were doomed not to be permanent, for it was always a difficult matter to keep the Danes from aggressive movement.

Hence the reign of Edward was largely taken up with the establishment of a real supremacy over the greater part of the Danelagh, a policy which was practically forced upon the Saxon king and was carried out with great efficiency by the energetic co-operation of the Lady of Mercia, who, like Edward himself, must have inherited her father's military talents and his capacity for inspiring enthusiastic devotion.

Fortified burhs

The great feature of the campaigning was the appropriation of the system borrowed from the Danes themselves of establishing fortified posts or burhs either at strategic points or where villages had already begun to develop into important towns. The conquest, however, did not mean the expulsion of the Danes, but little more than their effective acceptance of the supremacy of the Saxon king.

Shires

Mercia, like Wessex, was parcelled out into shires; but beyond Watling Street the shire was the district appertaining to a Danish military centre such as Leicester or Derby; and it would appear that south of Watling Street the shire was the district appertaining to one of AEthelflaed's boroughs. There was no longer an "ealdorman of Mercia"; but the shires did not get an ealdorman apiece; and in the Danelagh the name of earl replaced that of ealdorman, the earl being apparently in most cases a Danish jarl.

Submission of the Scots and Picts

About the year 921, when AEthelflaed died, the absorption of Mercia and East Anglia was completed; and before Edward's death, probably in 924, the kings of Wales and of the North had "taken him to father and lord"; among them Constantine, the grandson of Kenneth McAlpine, king of the Scots and Picts.

This so-called submission was put forward as the starting-point of the claim to the suzerainty of Scotland made some centuries later by Edward I of England. There is no really adequate ground for doubting that it actually took place, though the technical sufficiency of the evidence can fairly be challenged, since the only real authority for it, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, attributes the event to the year 924, and makes Ragnold of Northumbria a party to it, whereas Ragnold died in 921, according to other authorities. However the chances are that the chronicler was guilty only of some inaccuracy of detail; but Professor Freeman's view that from this time forward the sovereignty of the kings of England over Scotland was "an essential part of the public law of Britain" cannot hold water.

There was no more permanence in such a submission, if submission it can be called, than in the submission of Wessex to Offa of Mercia. Public law was not crystallised, and no one at the time would have dreamed of supposing that Scotland had placed itself permanently under the supremacy of England.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age