The Cato Street Conspiracy

In 1820 died the old king, who for the last eight years of his life had been entirely incapacitated by brain disease, to which total blindness was added. The Prince Regent became King George IV, but no change was thereby effected. The event of interest which followed immediately upon his accession to the throne was the formation of a wild plot known as the Cato Street Conspiracy.

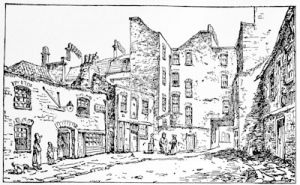

The plotters, who were persons of no importance and no influence, designed to murder the whole ministry at a Cabinet dinner. Information was conveyed to the authorities, and the conspirators, who offered a fierce resistance, were seized in a room in Cato Street. Four of them were executed, five were transported, and the incident was used by the Government as a proof of the anarchical spirit abroad which had made their repressive measures a necessity.

Public uneasiness was made the greater by the absence of any general sentiment of loyalty to the royal family, for which that family was itself responsible. The old king was held in respect, even in honour and in affection, by many of his subjects who could appreciate his sterling qualities and forgive, if they did not approve, his obstinacy and occasional wrong-headedness. His consort had been a pattern of domestic virtue.

But none of the sons of George III were distinguished by similar characteristics. For a long time the nation's hopes were fixed upon the Princess Charlotte, the daughter of the Prince of Wales, whose premature death in 1817 was generally lamented as a national misfortune. But when she died the old king had no legitimate grandchild living, and of his seven sons and five daughters the youngest was forty.

Who will be the heir?

The Prince Regent was held in general contempt as a bad husband and a bad father. The Duke of York had been notoriously mixed up with grave scandals. William, Duke of Clarence, and Edward, Duke of Kent, were at least comparatively respected, but they as well as the youngest brother, Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, were unmarried.

The fifth brother, Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, was the object of universal detestation, so much so that his accession to the throne might have sufficed to bring about a revolution, while the sixth brother had contracted a morganatic marriage; so that the future of the monarchy was a subject of grave apprehension.

The year after the Princess Charlotte's death the three unmarried brothers took wives, and the birth of the Duke of Kent's daughter, Princess Victoria, in 1819, provided a new object for the hopes of the nation to centre upon, since it was felt that the child's life alone stood in the way of a serious crisis in the early future.

The Trial of Queen Caroline

Almost the first proceedings of the new reign brought the Crown into fresh contempt. George IV, when Prince of Wales, though already secretly married morganatically, had taken to wife the Princess Caroline of Brunswick.

The two had long lived apart, and the princess had behaved at least with flagrant indiscretion for which George had given her as good excuse as any husband could. On her husband's accession to the throne she returned to England to demand formal recognition as queen, giving her due status in the Courts of Europe.

The Government replied by introducing in the House of Lords a bill to deprive her of her title and to dissolve the marriage. Popular feeling ran exceedingly high during the investigation of the charges on which the bill was based. The bill was carried on its second reading in the House of Lords by a majority of twenty-eight; four days later the majority for the third reading was only nine.

The Government,, now certain to be defeated in the House of Commons, withdrew the bill. Not contented with this effective victory, she attempted in the next year, of course unsuccessfully, to enforce her own coronation along with that of the king, an undignified performance by which she lost most of the popularity which the bill had procured for her.

Within three weeks of the coronation she was dead; but the whole of the proceedings had given birth to unlimited scandal, and had displayed the king's character in a singularly odious and contemptible light which destroyed almost the last shreds of popular respect for the monarchy.

Death of Castlereagh

Of more political importance than the elevation of the Prince Regent to the throne were the changes in the ministry which took place at the close of 1821 and during 1822. Lord Sidmouth - formerly Addington, the head of the ministry which had been responsible for the Peace of Amiens - who had been the author of the Six Acts, retired from the Home Secretaryship, in which he was succeeded by Robert Peel.

The Marquess Wellesley again joined the Government as Viceroy of Ireland. Then in August 1822 Castlereagh, who was just on the point of setting out to represent Britain at a European Congress assembled at Verona, committed suicide, and was succeeded at the Foreign Office by George Canning. Few ministers have been so intensely unpopular in the country as Castlereagh, and his death was hailed wilh unseemly acclamations of joy.

Posterity has been more just to him than were his contemporaries. To him more than any other man, at least after 1811 if not after 1808, was due the dogged persistence with which the French war was maintained; he, more than any other man, through good and evil report stood by Wellington in the Peninsula War.

Less of the responsibility for repressive measures at home belonged to him than was popularly believed; and some at least of the discredit attaching to the foreign policy of the country must be attributed to the popularity achieved by his rival and successor at the Foreign Office, George Canning, and to misrepresentations of Castlereagh's own action.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age