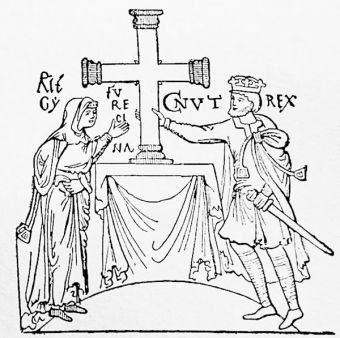

[Ed. The author spells the king's name Knut, though he is more commonly known to history as Cnut or Canute.]

At the moment when Knut made himself king of England his character appeared to be that of a bloodthirsty and treacherous tyrant. His ChristiÂanity was exceedingly fresh, since his father, Sweyn, had been savagely hostile to a faith of which he had some superstitious dread.

But once on the throne the young king curbed his barbaric instincts; only once in his later years did he allow anger to lead him to a foul crime, the sacrilegious murder of his cousin, Jarl Ulf. We may be in doubt how far his merits were due to policy and how far to a regenerate spirit, but their effect was entirely beneficial to England.

Edwy's murder

At the first Knut found an excuse for killing Edwy, the full brother of Edmund Ironside. He did not venture on the murder of Edmund's children whom he sent out of the country to Olaf, King of Sweden, who in turn passed the boys on to Stephen of Hungary, who brought them up. One of them became the father of Edgar the Atheling, of whom we shall hear again.

Marriage to Emma

Next, Knut married Emma of Normandy, the second wife and now the widow of AEthelred, although she was several years older than he. Possibly she may have learnt to detest AEthelred so thoroughly that she was willing to have the two sons she had borne to him overlooked; at any rate she left them to be bred up in Normandy, and accepted the hand of the Danish king of England on condition that if she had a son by him that son should be his heir.

Knut had not succeeded to the Danish throne, as he had an elder brother, Harald; but Harald's early death made him king of Denmark as well as of England; and in the course of his reign he also recovered Norway, which his father had won from Olaf Tryggveson, but which had broken away from Harald, and was ruled by another not less famous Olaf "the Thick," a stout warrior and energetic Christian, who was ultimately canonised.

Thus Knut was in his day the lord of a Scandinavian empire - the first king of England with a great continental dominion, though there were many after him. But, as happened often enough in early days, the empire depended upon the man who had made it, and broke up as soon as he himself was gone.

But Knut the politic meant England to be the basis of his empire; and he resolved to depend not on 'a tributary state' but on a loyal nation. Therefore after he had once made the weight of his hand and the firmness of his seat to be thoroughly felt, he set himself to the good governance of his realm. The traitors who had sought to curry favour with him by false dealing with Edmund met the stern doom they deserved.

The king levied a tremendous ransom from the country in his first year; but he used it to pay off the Danish host and sent it home, retaining only forty ships, whose crews provided his own huscarles [housecarls] or bodyguard. Nor did he rob his English subjects to provide land for his Danish followers, though for a very few of them he found sufficient provision in the forfeited estates of the traitors.

Knut's Earldoms

As, in later days, Norman kings pledged themselves to observe the "good laws of King Edward the Confessor," so Knut pledged himself to observe the good laws of King Edgar. But perhaps the most important change which he introduced was the principle of dividing the country into great earldoms, provinces much larger than the old ealdormanships.

Although the smaller earldoms were not abolished, the four or five great earls were magnates with much more power than had even been possessed by single ealdorman. Especially notable among the new earls was Godwin, a Saxon of apparently obscure lineage, whom Knut wedded to a kinswoman of his own, and to whom he presently transferred the earldom of Wessex, which at first he had retained in his own hands.

Knut is the subject of much picturesque anecdote which is too familiar for repetition here. His rule was strong, firm, and just, and the country prospered; but the events of most lasting importance connected with it belong also to the history of Scotland.

Cnut and Malcolm II of Strathclyde

The Scots king, Kenneth, together with his kinsman, the king of Strathclyde, was in that crew of kings who rowed King Edgar on the Dee; but his successor, Malcolm II, recognised no allegiance to AEthelred the Redeless. In one great raid upon Bernicia he had been beaten off with heavy loss, in 1006; but one of Knut's early misdeeds was the slaying of Earl Uhtred of Northumbria, who had been the victor in that battle.

In 1018 Malcolm again came down on Bernicia and won an overwhelming victory at Carham, the result of which was that Uhtred's brother Eadwulf ceded to him all Lothian; that is to say, Bernicia between the Tweed and the Forth; and from this time the Tweed formed the Scottish border. That fact was not altered by a northern expedition of Knut's, on which occasion Malcolm declined to fight and made submission, but retained Lothian. The submission, of course, counted precisely as long as a king of England was able to enforce it.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age