While Fairfax and Cromwell were organising the New Model, it was becoming increasingly clear that they would not be able to count on sufficient support from the Scots. The Leslies were much more inclined to think of returning to Scotland than of carrying their operations further south. Montrose in the Highlands flashed — no historian can avoid using the word — from point to point, falling swiftly and suddenly upon the Covenanting troops, harrying Argyle's own territory, and dispersing armies far larger than his own.

His victory at Inverlochy, early in the year almost warranted his promise to the king that before the end of the summer he would have won Scotland, and would be ready to aid Charles against his rebels in England. Even when Argyle was displaced by more efficient comÂmanders, the swiftness of Montrose's movements enabled him to outmanoeuvre them.

Naseby

But in England the generals of the New Model were determined to strike decisively. They realised that it was their business, not to capture and garrison strong places, but to bring Charles's main army to a decisive engagement and shatter it irrevocably. No one had attempted to shatter it before; Manchester, indeed, had deliberately avoided doing so. In June they started in pursuit, and came up with the Royalist army near Naseby, in Northamptonshire. The New Model did its work.

On the Royalist right Rupert's charge swept away Ireton's cavalry. On the Roundhead right Cromwell and his Ironsides swept off the Royalist horse. In the centre, the infantry on both sides fought fiercely, and the fortunes of the day were in doubt until Cromwell crashed back upon the enemy's flank while Rupert's headlong horsemen were still far away. The victory was complete. The Royalist horse escaped with curiously little injury, and Charles himself was forced to fly; but the Royalist foot were shattered beyond hope, of recovery. The whole of the baggage and all the munitions of war fell into the hands of the victors.

There was still an army in the south-west, under Goring's command, which Fairfax proceeded without delay to shatter at Langport. During the month which passed between these two battles, Montrose in Scotland had again defeated the best of the Covenanting commanders; and about a month after Langport he won at Kilsythe a victory which seemed to have brought Scotland under his hand. David Leslie hurried to Scotland, but before he was across the Border the fleeting character of Montrose's success was manifested. The Highlanders, whose desperate charges routed their foes, understood hand-to-hand fighting but not campaigning.

Philiphaugh

They scattered to their homes when Montrose descended to the Lowlands, and Leslie with four thousand men caught the great Marquis at Philiphaugh with a very much smaller force counted by hundreds. Of these some half fought with desperate courage; the rest hardly took part in the engagement.

Montrose's men were cut to pieces; some of them were massacred in cold blood; even the women and children belonging to Montrose's Irish troops were slaughtered. Philiphaugh was an ugly revenge for the ugly deeds of which the Irishmen had been guilty. In Scotland as well as in England the last chance of the Royalist cause disappeared.

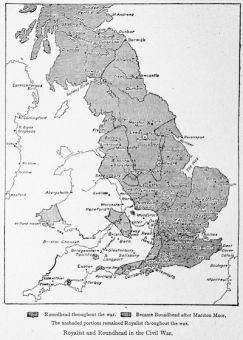

There were no more pitched battles. Charles had persistently followed the false policy of keeping his followers dispersed in garrisons all over the Royalist districts, instead of concentrating them to strike effective blows. The reduction of these garrisons now became the main business of the Roundhead force.

The great manor houses and halls which could bid defiance to the onslaught of casual troops were wholly unfitted to stand siege when siege ordnance was brought up against them. Resistance where resistance is obviously useless, and can mean nothing but a sheer waste of life, is not countenanced by the laws of war.

Only here and there, as at Basing Hall, did garrisons maintain a stubborn defiance in the face of palpably inevitable destruction; and except in such cases they were habitually permitted to surrender on honourable terms. The fierce spirit of hatred expressed in Macaulay's rousing ballad of Naseby had not yet come into play. The soldiers of the New Model were held under a stern discipline; robbery and outrage were practically unheard of.

But meanwhile the king, if he was unable to strike, was able to watch events. Victory in the field was out of the question, but the growing signs of dissension among his opponents gave him ample hope of victory by diplomacy. Within the year after Naseby, he placed himself in the hands of the Scots Army in England, as the most promising quarter from which to conduct his negotiations.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age