The Killing Time

Within five months of James's accession the strength of his position had been completely demonstrated. In Scotland the Scottish Estates were convened; and although they emphatically confirmed all the existing statutes for the security of Protestantism, they increased the severity of against conventicles, extending the application of the death penalty and introducing that worst period of the persecution known to Scottish tradition as the "Killing Time."

In May an English parliament assembled, and the House of Commons showed an overwhelming Tory preponderance, emphatic declaration on the king's part that he would defend the Church sufficed to secure the enthusiastic loyalty of the Commons. The revenue granted to Charles was renewed to James, and a further large grant was made for naval purposes.

Argyle

Meanwhile the extreme Whigs, the Exclusionists, who had taken flight from the country after their final rout, made their own desperate attempt. Argyle landed in Scotland and sought to raise an insurrection which was promptly crushed with complete ease; Argyle himself was captured and executed.

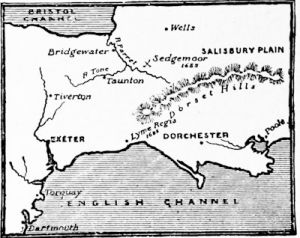

While the insurrection in the North was collapsing Monmouth landed at Lyme Regis, the south-western corner of Dorsetshire. He asserted his own legitimacy, while professedly leaving his title to the Crown to be decided by parliament. His pose was that of the champion of Protestantism and generally of the constitutional principles advocated by the Whigs.

The Battle of Sedgemoor

The appeal to Protestantism was effective among the rural population of Somerset and Devon, who flocked to his standard, ill enough tanned but full of enthusiasm. But the Whig magnates did not join him, and the destroyed such chance as he had by deserting his first position and proclaiming himself king.

Monmouth's valiant rustic levies met the king's troops at Sedgemoor, where they were completely routed in- spite of the stubborn valour of their resistance. Monmouth himself was caught and carried prisoner to London, where an Act of Attainder had already been passed against him, and he was as a matter of course executed after unedifying appeals for mercy, which were rejected, by the king with equally unedifying harshness.

Kirke's Lambs and Judge Jeffreys

The king's lack of nerve was shown not only by his alarm on the occasion of Monmouth's rising but by his encouragement of a vile vindictiveness in the punishment of the West Country which followed its very easy suppression. The savageries of "Kirke's Lambs," the troops just returned from Tangier, were only the precursors of the brutalities of Jeffreys, who was sent to conduct the judicial campaign.

Foul-mouthed abuse of accused persons and bullying of witnesses smoothed the way for the scandalous sentences which have stamped the memory of Judge Jeffreys with indelible 'infamy, and have given to his proceedings the name of the Bloody Assize. The number of persons put to death exceeded three hundred, and nearly three times as many were transported to convict slavery in the West Indies.

Unwittingly, however, Monmouth had done almost the worst disservice to James and the best service to Protestantism and constitutionalism that he could possibly have rendered, by getting himself executed, Monmouth was the rock on which the Whigs had split. The moment Monmouth was out of the way every one who was ill content turned his thoughts to the Dutch Stadtholder and his Stuart wife, the heiress-presumptive of the English throne.

Neither nobles nor gentry nor commons in England would take up arms to set the crown of England on the head of the son of Lucy Waters merely because a number of Whig leaders had chosen to pretend to believe in his-legitimacy. If James had had the wit to spare Monmouth as his brother would have done in the like case, James's antagonist would have found it exceedingly difficult to procure the intervention of the Prince of Orange. But vindictiveness blinded James to the more subtle policy, and by his own act he smoothed the way for his supplanter.

Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

Before parliament, which was prorogued in the summer, met again in the winter, other events had taken place which materially influenced the situation, For some time past Louis XIV, had been pressing heavily upon his Protestant subjects, who had already begun to seek safety in emigration.

In September be revoked the Edict of Nantes, the charter of Huguenot liberties, which for a hundred years past had secured at least a degree of toleration for French Protestants. The revocation let loose a storm of persecution, and Huguenot refugees began crowding to Brandenburg, Holland, and EngÂland. The antagonism to popery which had been quieting down was roused anew, in spite of the fact that the Pope and the Hapsburgs, Austrian and Spanish, both denounced the methods of the French king.

Parliament stands up to the king

James could have selected no worse moment for championing the cause of his co-religionists in his own country. The French king was employing his soldiery for the persecution, and that fact roused anew the general English hostility to a standing army, the more so when Englishmen who turned their eyes northwards saw what the king's troops were doing in the south-west of Scotland.

Nevertheless, James met his parliament with a demand for the increase of the standing army, the need of which he thought had been proved by the Monmouth rebellion, and with the announcement that he had nominated as officers men in whom he had personal confidence, but who also happened to be barred from all such appointments by the Test Act.

The change in the sentiment of parliament was at once apparent, though it was by a majority of only one that the House of Commons insisted on giving the question of the Roman Catholic officers precedence over that of supply. The victory over the Opposition brought waverers over to their side.

In the result a resolution was presented, in which the House engaged to release the officers from the penalties to which they had rendered themselves liable by taking office in defiance of the Test Act, but which in effect invited the king to cancel their appointment The House of Lords followed suit. The angry king denounced the conduct of both Houses and prorogued the parliament, which was not again assembled, though it was not actually dissolved till the midsummer of 1687.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age