In the chaos of Stephen's reign there had been little hope of obtaining Justice from any except ecclesiastical courts, which, as a natural consequence, enÂcroached upon the jurisdiction of the lay courts.

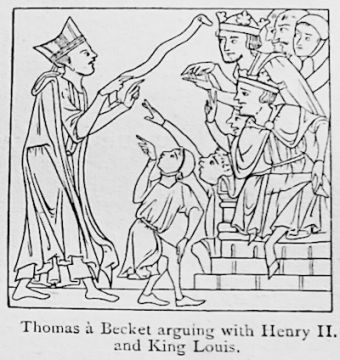

King Henry found that in all cases in which any person was concerned who belonged to the ranks of the clergy, including what was practically the lay fringe of that body, the Church claimed exclusive jurisdiction, and inflicted on clerics penalties which, from the lay point of view, were grotesquely inadequate. Royal expostulations were met by archepiscopal denunciations. The quarrel waxed hot.

The king was determined that the clergy should not be exempted from the due reward of their misdoings. In the Constitutions of Clarendon he propounded a scheme which he professed to regard as expressing the true customs of the kingdom. Becket was induced to promise to accept the customs; but not without justification he repudiated the king's view of what those customs were.

Criminous clerks

The clauses in the Constitutions which forbade carrying appeals to Rome and required the higher clergy to obtain a royal licence to leave the kingdom were hardly disputable. But the case for the "customs" broke down when the king claimed that criminous clerks should be handed over to the secular arm for further judgment after the Church had indicted its own penalties.

Becket, however, chose to resist the demand on the ground that a cleric as such was exempt from secular punishment in virtue of his office.

Becket in exile

The barons took the king's side and threatened violence. Becket yielded avowedly to force and nothing else. Having done so he obtained a papal dispensation annulling his promise. The king's indignation was obvious and justifiable. Becket persuaded himself that his life was in danger, as it really may have been; and he fled from the country to appeal to the Pope and the king of France.

In the course of the quarrel both sides had committed palpable breaches of the law. Now, with Becket out of the country, diplomacy at Rome, coupled with the logic of facts in England, might have secured the king complete victory; but he was tempted to a blunder. He had his eldest son Henry crowned as his successor.

Coronation was a prerogative of the Archbishop of Canterbury; the young prince was crowned without him. The Pope threatened to suspend the bishops who had performed the ceremony and to lay the king's continental territories under an interdict. Henry was alarmed and sought a reconciliation with Becket. At a formal meeting in France the quarrel was so far composed that Becket was invited to return in peace to Canterbury.

Becket's Death

He returned, but not in peace. He had hardly landed in England when he excommunicated the bishops who had participated in the coronation ceremony. The news was carried to the king, who was then in the neighbourhood of Bayeux. He burst into a fit of ungovernable rage.

Four knights caught at the words which he uttered in his frenzy, slipped from the court, posted to the sea, and took ship for England, where they at once made for Canterbury. They broke into the archbishop's house and charged him with treason. He flung the charge in their teeth. They withdrew, but only to arm themselves.

The archbishop's chaplains forced him into the cathedral where the vesper service was beginning. As he passed up into the choir the knights burst in with drawn, swords crying,"Where is the traitor? Where is the archbishop?" He turned and advanced to meet them.

"I," he said, "am the servant of Christ whom ye seek." One of them laid hands on him; the archbishop flung him off with words of scorn. They cut him down and scattered his brains on the pavement. Then they took horse and departed.

The murder of Becket gave him the victory which otherwise would hardly have been his. Henry's repentance was abject and sincere. Nearly eighteen months passed before he finally came to terms with the Pope; he evaded the extremity of submission, making a pretext for delay out of the expedition to Ireland, of which we shall presently speak further.

When he did come to terms he was able to maintain those claims for the independence of the English Crown which had been asserted by his predecessors. But he had to surrender on the question of the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts; and no encroachment was made upon those privileges called "Benefit of Clergy" until the dawn of the Reformation.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age