[By 1647] The Army was at odds with the Parliament; it was at odds now even with itself, for there had grown up in it a fiery democratic element, the element which became known as the Levellers, These men were imbued with the republican spirit, a contempt for social rank, hatred for the privileges of birth. They wanted the abolition of all such privileges; the destruction of the Monarchy and the Peerage.

Every man, in their eyes, had a right to a voice in the government of the country. Moreover, while they demanded toleration for Sectaries, most of them included Anglicanism in the general ban which nearly all Protestants extended to Romanists. Many of them were now denouncing Cromwell and Ireton, because those generals had hitherto set their faces against the republican doctrine and persistently advocated the toleration of Episcopacy.

If the Army broke itself up now, the king might come by his own; if the Royalists rose again they would surely be victorious. So Charles intrigued and plotted, and told the Scots that if they helped him to his throne in England he would establish Presbyterianism and make war upon the Sectaries. Scotland swallowed the bait, though not without opposition from Argyle, who, despite his faults, was not without some qualities of statesmanship.

In the spring of 1648 a Scots army, led by the Duke of Hamilton, crossed the Border, in arms for the King of England. Charles's intrigue bore fruit in a sudden blaze of Cavalier insurrections in Wales, in Cornwall and Devon, and in Kent and the south-east.

But the effect on the Army was not what the king had anticipated. While its chiefs, at the risk of their own popularity and to the danger of their own power, had been straining every nerve to keep the. passions of the soldiery in check, striving honestly and openly to arrive at a reasonable compromise which should be tolerable to every one; while they had been abstaining from violence, and had appealed to a show of force only when self-defence left them no alternative; the king had been playing with them, plotting for the destruction of the liberties for which they had fought. Compromise, agreements which depended upon good faith, could no longer be considered. There was one thing to be done at once — to stamp out the flame of insurrection. And then the Army and its leaders would be at one.

Fairfax took charge of the insurrection in the south-east, suppressed it in Kent, and held the main body of the insurgents shut up in Colchester. Cromwell flung himself into Wales. By the time that he had crushed resistance there the Scots army, badly led and badly organised, was streaming into Lancashire. Near Preston, Cromwell fell upon the flank of the long advancing column, cut it in two, and destroyed it in a running fight which lasted for three days. Colchester surrendered to Fairfax.

The spirit which had led the conquerors in the first civil war to act always with humanity, and as a rule mercifully and even generously, was killed. This was a war wantonly stirred up, when the sword had already been sheathed and the king who had incited it was pretending to seek reconciliation The insurgents were treated as rebels, and large numbers of them were shipped off to servitude in the plantations of Barbados.

The first step had been taken; the insurrection had been stamped out The victorious troops were returning, determined to dictate their own terms, when the news reached them that the king and the Presbyterian majority at Westminster had struck their own bargain. The Army would have no more bargains.

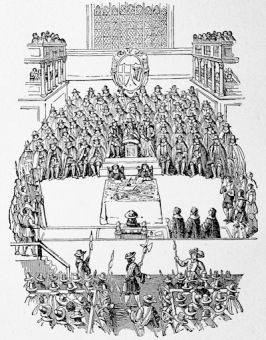

Pride's Purge

On the 6th December Colonel Pride and a body of musketeers took up their stand at the door of the House of Commons, arrested fifty of the members, and excluded a hundred more. The remnant, the Rump, as they were called, then assumed the functions of parliament. On the 4th January, they declared themselves, the sole sovereign authority in the country, and pronounced that their enactments had the force of law. whether the Crown and the Peers assented or no.

But behind this there was a more terrible determination. While the king lived there could be no peace. Charles had wrought treason against the nation; it was he who had deluged the land in blood, he who had foiled every attempt to establish a basis, for a lasting peace.

The king must die, not because a republic was better than a monarchy, not because the Crown was in itself an evil, but because Charles, personally, was an impossible king, and while he lived neither a republic nor another king were possible. As for the justification, let the Blood of the Saints testify. If the king were amenable to no human law, should the servants of the Lord be therefore debarred from acting as the instruments of His vengeance?

The trial of King Charles

So reasoned Cromwell and the Army. Yet ail should be done at least with a semblance of law. The Rump, as self-constituted sovereign, appointed a High Court of Justice to try "the man Charles Stuart." The king took his stand on the plain and obvious fact that such a court had no conceivable authority. He refused to plead. No one could even pretend that the authority of the Court rested upon the will of the nation any more than it rested upon law.

The nation stood aghast, half paralysed, while Fairfax and many others who had been appointed on the Commission refused to take part in the proceedings. The responsibility lay with those who had the power to enforce their way, and did not fear to do what they had persuaded themselves was their duty. In the eyes of the nation the king had committed no crime; now he played his part with a sincerity and a dignity which carried the popular sympathy to his side; and which for all time has clothed the figure of King Charles the Martyr with a halo of reverential pity.

But the stern men who had doomed him did not shrink; for them he was the enemy of God and of the people. The Court pronounced sentence of death, and England saw the head of its' king fall under the executioner's axe.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age