In strong contrast to Henry VII, stained, to the public eye, by the sordid craftiness of his later years, stood the brilliant young prince who succeeded him on the throne; a goodly youth, a champion in all manly sports, of a notable versatility, highly accomplished, a scholar and a lover of letters, the whole nation acclaimed Henry with enthusiastic anticipations. His first actions added to his popularity since he at once struck down the worst agents of his father's extortion, the notorious Empson and Dudley.

It mattered not much to the public that the actual charges on which they were put to death could scarcely be sustained. They met with their deserts, and no one inquired" too curiously into the technical justification. The pomp and festivities of the young king's marriage with Katharine of Aragon encouraged the general rejoicing.

The European monarchs also rejoiced. Ferdinand of Spain and the Emperor Maximilian were extremely experienced politicians, who hoped to find in the young monarch's warlike ambitions a means whereby they could use his innocence to achieve their own ends' at his expense, their immediate object being the depression of France. There was in England an inclination to revive the martial glories of the past at the expense of France, and before long it seemed that the old schemers would have their way. Henry was drawn into a league, and plunged into a French war in 1512. His prize was to be the recovery of Guienne. This was the bait offered him by Ferdinand and Maximilian, though neither of them had the slightest intention of helping him to get it.

The first expedition despatched for the attack on Guienne was a mere fiasco. But the failure brought to the front the minister who, in .the public eye, was to dominate Henry's policy almost throughout the first half of his reign. Thomas Wolsey, the son of a grazier, or of a butcher according to his enemies, had been sent to Oxford at an early age; and having distinguished himself there, entered the household of Lord Dorset as a tutor. By Dorset he was brought to the notice of Bishop Fox, one of the great ecclesiastical ministers of Henry VII. Fox introduced him to the king, who soon discovered his unusual abilities.

When young Henry came to the throne Wolsey was attached to the Council, probably as the right-hand man of Bishop Fox, who remained the official representative of the old king's policy; while the war party who hoped to carry the king with them was headed by the Earl of Surrey, Thomas Howard.

But Henry had an unfailing eye for character, and he perceived in Wolsey precisely the man he wanted - a man ambitious for England and for himself, but one whose birth and conditions precluded him from becoming dangerous to the Crown; a man with an infinite grasp of detail and an infinite capacity for labour, but with a breadth of view which completely removed him. from the class of merely capable officials.

Wolsey's conception of policy appealed to the king, and Wolsey would relieve him of all the troublesome part of carrying it out. Since the war had been embarked upon, it was Wolsey's immediate policy to carry it through with efficiency. There were to be no more fiascoes, and a vigorous campaign was arranged for 1513, in which the king himself took part. His zeal for military glory was rewarded by the capture of Terouanne and Tournai. But the great event of the year was the battle of Flodden.

Flodden

The relations between James IV of Scotland and his brother-in-law were strained in spite of the treaties of friendship struck in the previous reign. There were mutual charges of piracy between English and Scottish sea captains; there were quarrels about border raids; there were squabbles about the alleged dower of Queen Margaret.

James had always refused to repudiate the old alliance with France, and his fatal passion for knight errantry was roused by the French queen's appeal to him to strike a blow on English ground as her knight. The bulk of the Scottish nobility went always ready for a fight with the English, and Henry had hardly sailed for France when James crossed the Border with a great army.

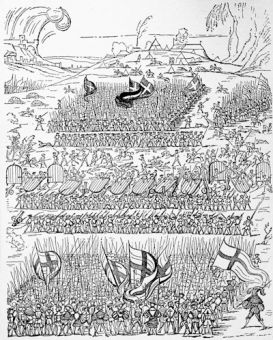

The course of the battle

The defence of the kingdom had been left in the hands of Queen Katharine and Surrey. James advanced to Flodden Edge in Northumberland, having secured the castles on his rear which threatened his communications. Surrey, having gathered a considerable force, challenged the Scots to descend from the strong position they had occupied and fight him on the plain. The Scots were completely masters of the situation, and declined.

Surrey, whose movements were masked by the hilly country, marched north towards Berwick, leaving the Scottish army on his left, then wheeled, crossed the river Till so as to cut off any retreat of the Scots army, and advanced southwards again towards Flodden. James might have held his own ground and laughed at Surrey; but in a moment of infatuation he chose instead to descend from his position and give battle. The conflict resolved itself into a furious hand-to-hand struggle.

The wings of the Scottish army were broken, the centre was enveloped, the flower of the Scottish nobility were cut to pieces, and James himself was slain as Harold and his brothers had been slain at Senlac. The effective military force of Scotland was utterly ruined; and Scotland, with a babe in arms for its king, was once again plunged into the miseries of a prolonged regency. It was fortunate for her that Surrey was quite unable to follow up his victory by a counter-invasion.

Henry's successes had by no means been to the liking of Ferdinand, who saw that a continuation of the war was not unlikely to secure to the English ting the lion's share of the spoils. Therefore he drew off Maximilian, and those two deserted their English ally and made peace on their own account with France. But Wolsey had learnt in the school of Henry VII to pursue his objects by diplomacy rather than by war, and he counteracted the desertion of Ferdinand and Maxmilian by negotiating an alliance between England and France, regardless of the traditional sentiment of hostility between the two countries.

His immediate intentions were frustrated, because although the French king, Louis XII, married the English king's younger sister, Mary, his consort having just died, he himself died three months afterwards, and was succeeded by his cousin, Francis I, who was slightly younger than King Henry.

In the course of the next four years both Maximilian and Ferdinand died; with the result that Charles, the grandson of both of them, succeeded to the entire heritage of Spain, Burgundy, and' Austria, and was very shortly afterwards elected Emperor. Thus in 1519 three potentates dominated the world, of whom the eldest was eight-and-twenty and the youngest was nineteen; and the domination of this same trio lasted for more than five-and-twenty years.

Wolsey the diplomat

The skill of Wolsey's diplomacy from 1515 to 1519 cannot be appreciated without an elaboration of detail and an intricacy of explanation impossible in these pages. We must be content to say that he outmanoeuvred both Ferdinand and Maximilian in their own game of diplomacy, and encouraged the former to check the aggressions of Francis in Italy, while he successfully kept England out of war. The one remaining important factor on the Continent was the Pope, Leo X; and Wolsey succeeded in making all the Powers realise that his own diplomatic ability made it extremely dangerous for any of them to incur the hostility of England.

The accession of Charles V to the Empire made the rivalry between Charles and Francis one of the two dominant features of continental politics. The other was the rupture of Christendom, following upon Luther's revolt against the Papacy; but this did not immediately come into play. In 1520 Wolsey found both Charles and Francis eager to secure the English alliance, while it was his own object so to avoid committing himself to either, that England might be able to act as arbiter between them, and might extract her own advantage out of that position.

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

Hence that year witnessed the ostentatious display of cordiality between the kings of England and France at the famous meeting of the Field of the Cloth of Gold — and also a quite unostentatious meeting in England between the English king and Charles. The meetings left the real situation practically unaltered. Henry was the good friend and ally of both the continental monarchs, but neither of them knew which he would support if they should come to blows.

While the collision was still approaching, the immense ascendency which the Crown had achieved in England was demonstrated by the tail of the Duke of Buckingham the nobleman who stood nearest to the Crown in virtue of his descent both from the house of Beaufort and from the house of Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, the youngest son of Edward III. The king can have had little enough to fear from him; but he was representative of the hostile attitude of the nobility to Wolsey, whose arrogance was particularly insulting in their eyes.

The Duke had used language which could be interpreted as implying treasonable sentiments. He was tried by his peers and was condemned without hesitation, though the pretence that there was any real treason was merely ridiculous. It was made manifest that the peers at least were entirely subservient to the Crown. By the end of 1521 Charles and Francis were at war in spite of all Wolsey's efforts. A few months later, England, as the ally of Charles, had declared war upon France. Wolsey in the interval had been disappointed by a papal election in which he had been passed over. Eighteen months later there was another papal election, and Wolsey was again passed by in favour of the Cardinal de Medici, who took the name of Clement VII.

On both occasions Charles had promised to use his influence in Wolsey's favour, and on both he conspicuously failed to do so. Wolsey himself had always been rather inclined to favour Francis rather than Charles but had taken the course which he knew his master would prefer. But after the election of Pope Clement, he was probably planning for a revival of the French alliance. In his own day he was certainly credited with having been intensely set upon the acquisition of the papal crown.

Possibly he did not realise that he was a greater power as Henry's minister than any pope could be; but possibly also he was already conscious that a minister of Henry held office by a precarious tenure.

The Amicable Loan

In 1525 the French king met with a great disaster and fell into the hands of his enemies at the Battle of Pavia. England had put little energy into the war, but Henry was anxious to take advantage of Pavia to wring Guienne from France. He wanted money for the purpose. The war was not in the least popular in the country, and Wofeey feared that to ask parliament for supplies would be exceedingly risky. Instead, he resorted to what was called the Amicable Loan, which was nothing more or less than an illegal tax.

Perceiving ominous signs that a storm of resentment was brewing, Woleey dropped the Amicable Loan and called for a Benevolence. London met the demand by an appeal to the statute of Richard III. by which benevolences were declared illegal. The king saw how matters stood, and rose to the occasion after his own fashion.

He withdrew the demand, claiming and receiving credit for a noble generosity, while Wolsey, execrated by the people, became a secret object of the royal displeasure; not because of what he had done, but because of what he had failed to do. Wolsey fried to pacify the king's resentment by presenting him with his palace at Hampton Court. The king accepted the present, and the Cardinal's favour was outwardly unimpaired.

But the fiasco over the loan reduced the French war to an absurdity. Wolsey achieved his own present end, a pacification with France, which was to pay a heavy indemnity. The defection of England forced Charles to make peace. Events were steadily tending to bring England and France into close friendship and to isolate Charles.

But Charles was left in a dominating position in Italy, a position alarming to the Pope; the antagonism of Pope and Emperor led in 1527 to the capture and sacking of Rome by Charles's troops, and the Pope was held in the hollow of the Emperor's hand. But before we pursue the story of the reign further, we must examine the progress up to this period of the movement to which we give the name of the Reformation, which was now becoming a foremost factor in European politics.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age