Whether Henry V, if he had lived to the age of Edward I, could have succeeded in the policy of uniting England and France on the lines of the treaty of Troyes, is sufficiently doubtful; when he died at the age of thirty-four, the possibility of success disappeared. A king with a character and genius equal to Henry's was needed to carry out his work effectively.

The Duke of Bedford

The man who was actually left to carry it out was hardly the inferior of Henry himself, whether in character or in military or political ability. But he would seem to have lacked the magnetic personality of Henry the Conqueror, and he was not a king. John, Duke of Bedford, though he was trusted and admired on all hands, yet lacked the royal authority; and lacking it, the task for him became impossible. And yet it was not till his death, thirteen years after that of Henry, that the sheer impossibility of it became clear.

It is clear enough that the conquest of a united France by England could only have been accomplished by a miracle. Henry himself would hardly have achieved what he did if the murder at Montereau had not turned the new Duke of Burgundy into his active ally.

If the Dauphin Charles had been an able and vigorous prince, if he had striven for a real reconciliation between Burgundians and Armagnacs, instead of lending himself to the monstrous treachery which almost justified Burgundy in siding with a foreign conqueror, Henry's conquest might have been restricted to Normandy. But even before and still more after Montereau, the France with which the English had to deal was disunited; and while Burgundy was definitely on the side of England, it was always possible that the Plantagenet might overthrow the Valois claimant of the French throne.

Jacquelaine of Hainault

But the Burgundian alliance was immediately weakened by the action of Humphrey of Gloucester. The Duke of Brabant was a kinsman and ally of Philip of Burgundy. He had got possession of Hainault by marrying its heiress Jacquelaine, who not without reason sought a divorce from him. Gloucester wished to marry her and get Hainault for himself. Philip espoused the cause of the Duke of Brabant. Jacquelaine got her divorce, but only from the ex-pope who had been deposed by the Council of Constance. Nevertheless Gloucester married her, and tried to recover Hainault from the Duke of Brabant. It was all that Bedford's diplomacy could effect to prevent an open rupture between England and Burgundy.

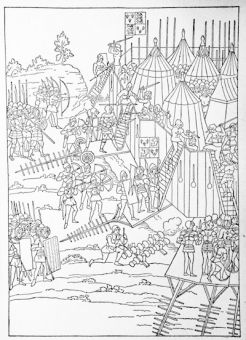

Nevertheless for some time the slow process of conquest went on. The unhappy King Charles VI died just after Henry V; and the north of France recognised the infant Henry VI as king, and Bedford as regent. The south recognised Charles VII. Bedford won brilliant victories at Crevant and Verneuil; and in 1428 the siege of Orleans began.

Joan of Arc

Through the winter the siege went on, but it was not destined to be successful. France was redeemed by the heroism of a girl whom the English burnt as a sorceress, since otherwise they must have acknowledged her for God's angel sent for the deliverance of France. Modern wisdom escapes the dilemma by classing her as an unexplained psychological phenomenon; but the Middle Ages explained such phenomena by referring them to the direct intervention of God or the Devil.

But however we may elect to interpret Joan of Arc, we may at least be perfectly certain that her interpretation by the English and by Shakespeare was hideously and fearfully wrong. To the court of Charles VII at Chinon came a country maid, Jeanne D'arc, from Domremy, in Picardy. To her, she said, had come voices and visions, bidding her arise and save France.

For herself she asked nothing but to be suffered to obey the Divine command. Common sense scoffed, but common sense was somehow silenced. She got her way, and sallied from Chinon at the head of an armed force. She reached Orleans and entered it without difficulty, for the investment was incomplete. The garrison became inspired, and upon the English fell a terror of they knew not what; art magic they called it.

The Maid could not be resisted. The English force had never been strong enough to effect a complete blockade now it could not even hold its own against the onslaughts of the garrison The siege was broken up. At Pataye, Joan met the English in the open field and routed them. Then through a hostile country she accompanied Charles to Rheims to crown him King of France. Her work as she understood it was now done, but Charles could not dispense with so valuable an asset. He would not suffer her to depart as she herself desired.

Fall of the Maid of Orleans

For a year she continued to lead French forces to victory in repeated skirmishes and sieges; but at last she fell into the hands of the Burgundians, through the treachery, it was said, of jealous Frenchmen. By a French ecclesiastical court she was tried and condemned on charges of heresy and witchcraft.

Then she was handed over to the English for the execution of the sentence, and was burnt at the stake to the eternal shame of every one concerned; of the judges who condemned her, of the English who slew her in a fever of superstitious terror, of the contemptible king who left her to her doom without stirring a finger to save her. The death of the Maid of Orleans is the one blot on the fair fame of the Duke of Bedford.

The cause for which the Maid died was still very far from being won. But she had wrought a vital change. She had revived the spirit of patriotÂism in the French, and destroyed the self-confidence of the English. Success departed from them. They fought on. obstinately, but no longer with the old assurance of victory. Burgundy was less than half-hearted, and began to be anxious to put an end to the war.

At last, in 1435, there was a conference at Arras, at which it was proposed on the part of the French that England should retain the Calais Pale, Normandy, and Guienne, but should resign the claim to the French throne. Yet English obstinacy rejected the terms. Burgundy in disgust threw up the alliance, and France was at last united in resistance to England, which by the death of Bedford in 1436 lost the one man who might have saved it from the woes to come.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age