The death of Edward I put an entirely new complexion upon the prospect of Scottish independence. The old king had made up his mind to punish the fresh revolt with an iron hand and to bring Scotland under his heel. A successor of the same quality as himself might have carried out his plan, though it may be doubted whether he could have effected a permanent pacification of Scotland.

But Edward II was of an altogether different type. Devoid of patriotic or kingly ambition, the young Edward had little thought except for his amusements and the gratification or the wealth of the favourites by whom he was surrounded. Moreover, as often happens with a masterful ruler, the great Edward had been served, latterly at least, by men who were efficient instruments for executing his will but were not capable of relieving his successor of the responsibilities of government.

So instead of carrying out his father's plans, Edward II contented himself with a mere military parade, dropped the conquest of Scotland, left its government in charge of the Earl of Pembroke, and retired to England. No one troubled about Scotland, since the whole of the baronage immediately found themselves entirely taken up with the personal rivalries and jealousies which were let loose by the conduct of the new king.

So Bruce continued his raiding, held in check only by the various castles which the policy of the first Edward had filled with English garrisons, and by the hostility of nobles who were either involved in the blood-feud with the Comyns or, for one cause or another, were irrevocably committed to the English side. Those who were not so committed either sat still and awaited events, or, as one success after another attended the arms of the adventurer and the band of brilliant fighting men who had attached themselves to him, became open adherents of King Robert.

Each new feat of arms achieved by the king himself or his brother Edward, by James Douglas or Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, brought in fresh supporters; while no similar successes attended the English, who sat sullenly in their castles until one after another was surprised, and, being captured, was levelled with the ground. For the Scots could not afford to lock up their own fighting men to garrison the castles, nor would they run the risk of their being reoccupied by the English.

In 1310 Edward was stirred up to lead an invasion into Scotland; but he found no one to fight, the country was laid waste before him, and he retired in inglorious discomfiture. In 1311 and 1312 the Scots took the offensive and raided the northern counties of England. Then Perth was surprised in January 1313, and Roxburgh a year later, by Bruce himself and by Lord James Douglas respectively.

Before Easter Randolph had surprised Edinburgh, scaling the precipitous rock by night. Stirling had already been invested, and was now the only fortress of importance which remained in English hands; moreover the commandant had pledged himself to surrender unless he were relieved by the Midsummer Day ensuing.

Build-up to Bannockburn

The fall of Stirling would mean that the last fragment of Edward I's conquest of Scotland would vanish. Even Edward II awoke to the necessity for action. A superficial reconciliation had just been effected between the king and his barons; and, though some of them still declined to join him in person on a Scottish campaign undertaken without the express sanction of Parliament, he led a mighty army across the border in June 1314, magnificent in equipment and attended by a vast baggage train. He had a short week in which to reach Stirling before the hour should arrive when it was pledged to surrender unless relieved. The great host rolled to the north-westward in a hasty and ill-managed march.

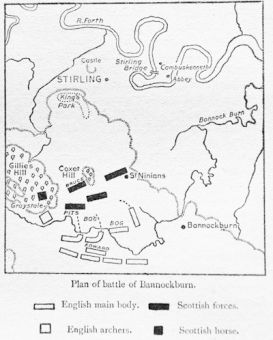

King Robert knew that the crucial hour had come, and posted his comparatively small force on a carefully selected position, the field of Bannockburn, covering the immediate approach to Stirling. Wallace had staked all on the field of Falkirk, which had come near to being a decisive victory for the Scots. Bruce himself had been present at that battle, and fully understood how it was that Edward had turned it into a decisive English victory. Falkirk was not be repeated at Bannockburn, since Bruce rightly calculated that there was with the English army no commander possessing the large experience and the technical resource of Edward I.

It was a moral certainty that the English with their huge force of men-at-arms, would rely upon the customary medieval tactics, and endeavour to crush the Scottish infantry by the shock of charging squadrons. He himself must rely, like Wallace, upon the stubborn valour of his footmen; since he, like Wallace, had no masses of cavalry and few archers.

Therefore he had to guard against the possibility of having his flank turned, and against a repetition of the archery tactics. The position chosen gave Bruce what he needed, a narrow front where his soldierly could be massed, with broken and boggy ground on the flanks which secured them from being turned. Boggy ground on the front itself would minimise the shock of the charge; and where it was not boggy it was carefully prepared with the iron spikes called calthrops, and with covered pits, so as to produce a similar effect. The bulk of Bruce's cavalry too were dismounted, and disposed so as to strengthen the line of infantry, while only a picked squadron was retained to strike suddenly and swiftly when occasion should arise. The Scots were outnumbered by more than three to one, but on the field the English could not bring their numbers into play.

The Battle of Bannockburn

Such was Bruce's plan. When the advancing hosts of the English appeared, the incidents of the day gave a foretaste of the coming struggle. A detachment of English horse made a dash round the Scottish flank in order to reach Stirling and effect the technical relief. A detachment of Scottish foot was just in time to intercept it and drive it back in rout. An English knight, Henry de Bohun, seeing the Scottish king riding almost unarmed along the Scottish line, charged down upon him. At the critical instant Robert swerved his palfrey, and as De Bohun crashed by, clove his skull with his battle-axe.

On the following day the battle went precisely as Bruce had designed. The masses of mail-clad horsemen were hurled against the Scottish front, crashing vainly upon the serried spears. The archers were thrown forward on the left, but no steps were taken to cover them, and almost with the first flight of the arrows the small squadron of Scottish horse burst upon their flank and cut them to pieces. With repeated charges, the English horse became a huddled, unmanageable mass; the Scottish infantry rolled forward in unbroken line; a band of camp followers descending the neighbouring Gillies' Hill was mistaken for a fresh Scottish host; and the great English army broke in a panic rout.

Consequences of Bannockburn

Never had the English met with a disaster so overwhelming; the fugitives were slain in heaps, though the small supply of cavalry made the pursuit only desultory. Numbers of prisoners and vast spoils fell to the conquerors.

On the field of Bannockburn the independence of Scotland was decisively won, though fourteen years were still to pass before England acknowledged the fact by the treaty of Northampton. During those fourÂteen years the Scots became the aggressors. Berwick, the only corner of Scottish soil still held by the English, was captured; and year after year Douglas and Randolph harried the north of England, while the unfailing misrule in the southern country prevented any organised effort to retrieve what had been lost.

Edward himself had been murdered, and his queen Isabella with her paramour Mortimer were ruling England in the name of young Edward III, when the government at last bowed to the logic of facts, and the treaty of Northampton acknowledged Robert Bruce as king of the independent Scottish nation. But the great liberator's life was already drawing to a close, and a year later he died, leaving the crown to his son David II, a child of six years old.

Robert the Bruce, king of ... Ireland?

A curious episode followed the battle of Bannockburn. For nearly a hundred and fifty years the King of England had been titular lord of Ireland. Within the small group of counties known as the English Pale, English government and English law and customs prevailed. Outside the Pale the north of Ireland remained almost entirely Celtic, the De Burghs, the Earls of Ulster, being almost the only great Norman family.

But, in the south, Norman families, most notably the Geraldines and the Butlers, extended their dominions and ruled almost as independent princes; very much criticised in their sympathies though retaining some of their Norman traditions. Outside the Pale the central government was practically powerless. After Bannockburn, the O'Neills and O'Connells, the most powerful of the northern clans, offered the crown of Ireland to Robert Bruce. That shrewd prince declined, but the proposal to substitute his brother Edward was accepted.

The Bruces went over to Ireland to win the crown, and obtained a very general support from the native chiefs. The Normans, however, stood by their fealty, and while the Bruces were victorious in the field, they were unable to reduce the Norman strongholds. Still Edward Bruce got himself crowned King of Ireland, and was left by his brother to establish himself in his kingÂdom. His reign was brief, for a vigorous English governor arrived in the person of Roger Mortimer.

In a fight at Dundalk Edward was defeated and slain, and Ireland thereafter was more or less reduced to submission; but if the episode had any permanent effect, it was to diminish rather than extend the authority of the central government; and the efforts of the English lieutenants were still mainly directed to vain attempts to prevent the Celticising of the English in Ireland.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age