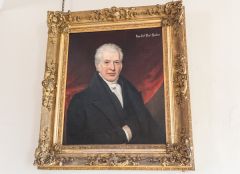

The Workhouse is a huge building, or, rather, a set of connected buildings, constructed in 1824 by Rev John Becher of Southwell as a residence for the poor. Becher's workhouse was one of the first in what later became a nationwide system of housing for poor people. The system invoked by Becher was adopted in the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act to create a harsh welfare system through the erection of similar workhouses across the country.

Before Becher's time, each parish was responsible for supporting the poor in their own homes. Becher and his associate, George Nicholls, created a system which invited parishes to pool their resources to operate housing for the poor on a local or regional level.

The Workhouse - originally called the Thurgarton Hundred Incorporated Workhouse and later the Southwell Union Workhouse - was home to 158 inhabitants, drawn from 62 nearby parishes. The inmates used the Workhouse as a place of last resort - and it's not hard to see why when you consider the life they were expected to lead.

Men, women, and children had separate quarters, which meant that families were split up and not allowed to meet. The children received a rudimentary education, and some were made to work.

Becher's philosophy was that the workhouses should be a deterrent to an idle or profligate lifestyle, and the harsh reality of workhouse life was meant to encourage people to avoid this port of last call if at all possible. His theory was that people could find work if they really wanted to, and most indigent people were really just lazy.

Inmates were divided into categories; those too old or infirm to work were called Blameless and tended to be treated with compassion.

But woe betide those who were thought capable of work yet unemployed. They were called 'idle and profligate able-bodied' and were expected to work for their keep, occupying their days in such tedious tasks as breaking up rock for road building or picking apart strands of rope. Everyone wore uniforms and life was intentionally kept dull, monotonous, and strictly controlled.

Becher aimed at moral improvement; by dint of tedious, hard work idle folk were supposed to be converted to a more upright lifestyle. Rules were strict and transgressions were harshly punished. Life was regimented and strictly controlled, under the watchful eye of a paid Master and Matron.

Following the example of Becher's Workhouse, hundreds of similar houses were opened across the country. The Southwell Workhouse was in operation for over 150 years. Then in 1929, a new Poor Law was introduced, and many of the old workhouses were converted into hospitals or social housing. The Workhouse provided temporary accommodation for the homeless until 1976, and part of the site was converted into a residential home for elderly people.

In 1997 Southwell Workhouse was in danger of being converted into flats when the National Trust stepped in to buy it. It remains the least altered poorhouse in the country, and a symbol of a way of life for thousands of our ancestors. An audio guide gives modern visitors a chance to 'meet' workhouse inhabitants and learn about their lives.

Visiting The Workhouse

I didn't know what to expect when we visited The Workhouse. Though from a distance it simply looks like a large factory, as you get closer it begins to look more and more like a prison, an impression that is only enhanced when you pass through the visitor entrance into a series of inner courtyards and begin to realise just how segregated and isolated the inmates must have been.

Make no mistake, they were 'inmates', not precisely prisoners in the strictest sense of the word, but not far from it. Life must have been terribly difficult for those forced to seek shelter in places like The Workhouse.

Around the inner courtyards are a series of small buildings housing a laundry, drying room, bakery, water tank, and an infirmary. One of the most interesting of these subsidiary buildings is the bakery, marked as a privy on the original plans for the site. It was only when the National Trust discovered a mysterious key that the hidden bakery was opened for the first time in decades.

The tiny exercise yards, with a very simple outdoor privy in one corner, are overlooked by the warden's chambers so that even at 'rest' the inmates were watched over like criminals.

It is easy to come away from The Workhouse appalled at the conditions that the poor were forced to live under. And yet, you have to ask yourself, were conditions in the countryside any better?

Most people came to the Workhouse because they had no alternative; work was hard to come by, and there was little of what we might now call social care. As harsh as life was at Southwell, it could also be harsh in the world outside the Workhouse.

I highly recommend the Workhouse for schools and families. The National Trust has done a good job showing what life was like for those who lived here, and it is a real eye-opener that should help visitors get a real sense of how difficult life was in the Victorian period if you were poor or simply unfortunate enough to have to rely on workhouses like this to survive.