NOTE: The Royal London Hospital Museum closed in 2020. To date, no plans have been announced for its reopening or to inform the public about the fate of its historical medical displays. We will update this page if there is any indication that the museum will reopen, but for now, please DO NOT make plans to visit.

UPDATE: The former museum collections can be accessed by appointment with the Barts Health NHS Trust Archives.

What do Jack the Ripper, Edith Cavell, and Joseph Merrick (the Elephant Man) have in common? They are all closely connected to the Royal London Hospital Museum in Whitechapel. The museum holds a remarkable collection of historical artefacts covering medical treatment in London's East End since the 18th century, including some of the earliest x-ray machines in Britain.

History

The roots of the Royal London Hospital go back to 1740. at that time there were five hospitals in London offering free medical care to the lower classes. None of the five, however, was in the growing east end, a quickly growing - and very poor area of the city.

On 3 November 1740, the London Infirmary opened on Featherstone Street in Moorfields, offering free medical care, with the cost carried by annual subscription fees given by philanthropic Londoners. The hospital moved into a larger building on Prescot Street in 1741. It changed its name to the London Hospital in 1748.

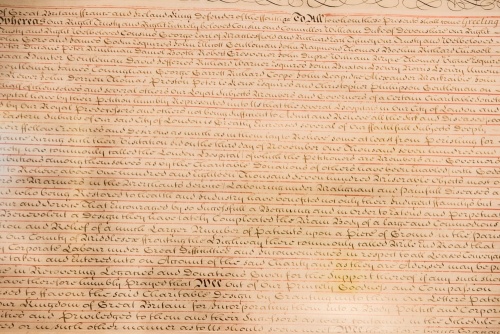

In 1757 the hospital moved into new purpose-built premises at Whitechapel Mount. In the following year, 1758, the hospital charity acquired a royal charter, which, though it sounded prestigious, actually meant that the hospital could now be operated as a legal entity. The royal charter did not add 'Royal' to the hospital's name; that didn't happen until 1990 when Elizabeth II visited the hospital as part of its 250th anniversary celebrations.

The 1758 royal charter is on display in a glass case in the museum. It gives the Hospital board of governors the right to buy and lease land without having to name individual people as trustees for each transaction. The result was that they could easily expand the hospital's estate.

In 1785 the London Hospital Medical College was formed, making it the first medical school in England connected to a hospital.

The Elephant Man

In 1886 Joseph Merrick, known as 'The Elephant Man' for his rare physical deformities, came to the Royal London Hospital as a patient under the care of the surgeon Frederick Treves. Merrick would spend the rest of his short life at the hospital after Treves rather conveniently overlooked the hospital rules so that he could stay on.

Merrick's deformed skeleton is kept on display for hospital students, but an exact replica is in the Hospital Museum along with Merrick's hat and the veil that he used to hide his face in public. You can also see a letter written by Merrick while he was living at Royal London Hospital, and a copy of a portrait showing Merrick in his 'Sunday Best' suit, taken in 1889. There is also a model of Mainz Cathedral made by Merrick in his spare time.

As for Treves, he went on to become the first president of the London Hospital Clubs Union in 1892 and became famous enough that he was called on to treat Edward VII.

Edith Cavell

Edith Cavell was an English nurse who worked at London Hospital before serving in occupied Belgium during WWI. There she helped wounded Allied soldiers escape to safety until she was captured by the Germans and shot as a spy.

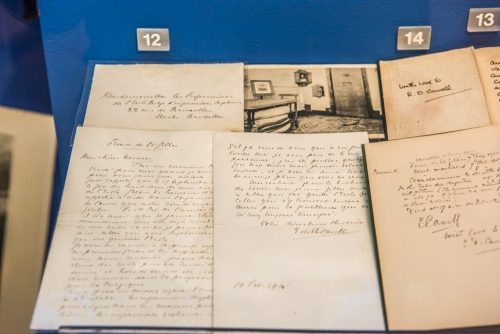

The poignant exhibit includes the wooden cross from her grave and a Book of Common Prayer which she had with her in prison. It is inscribed by Cavell to her cousin Eddie. There is also a facsimile edition of Thomas Kempe's 'Of the Imitation of Christ' with hand-written annotations made just before her death.

Then there is her final handwritten letter to her nurses, dated 10 October 1915. The letter was written in French from St Giles prison two days before her execution by firing squad. Also on display are several souvenir items manufactured after her death to take advantage of the public interest in her story.

Jack the Ripper

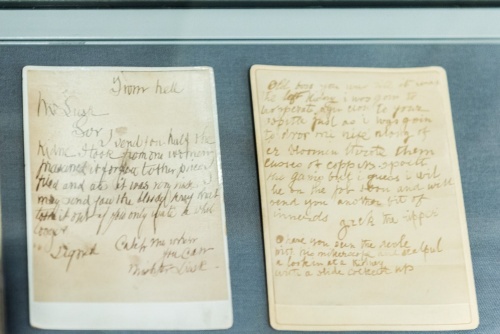

On Sunday 30 September 1888 Catherine 'Kate' Eddowes was brutally murdered in the sordid streets of Whitechapel, not far from the London Hospital. Shortly after, a letter - later known as the 'From Hell Letter - was sent to George Lusk, Chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, with what appeared to be a piece of a human kidney.

The kidney was taken to Dr Thomas Horrocks Openshaw, a London Hospital surgeon and Pathological Curator for examination. Dr Openshaw's name was mentioned prominently in the newspapers in connection with the incident and on 20 October he received a letter addressed to 'Dr Openshaw, Pathological curator, London Hospital, Whitechapel'. The letter was signed 'Jack the Ripper'.

A copy of the 'Openshaw Letter' forms part of a compelling - and sometimes stomach-churning display on forensic medicine at London Hospital. Included are clippings from the Illustrated Police News covering the Ripper murders, a copy of the 'From Hell' letter, a sketch of the Eddowes crime scene and drawings of the victim's body and facial injuries sketched by Dr Gordon Brown.

Against the wall is a carbon arc electric lamp used to generate ultraviolet light. The lamp was used to treat King George V in 1928-29. After the king's recovery, the lamp was given to the Hospital where it was subsequently used to treat deficiency diseases such as rickets. Nearby is an odd machine looking like a cross between an early gramophone and a pressure-cooker. It is actually an x-ray unit made by the General Electric Company in 1934 and used with a fluoroscopic x-ray screen.

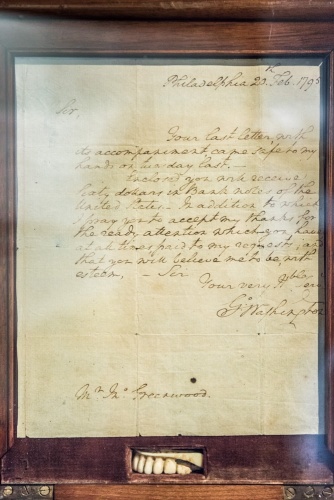

One very unusual exhibit is part of an upper denture made for George Washington, the first President of the United States. The denture was made by John Greenwood, and on display is a letter from Washington to Mr Greenwood enclosing payment for the false teeth. The teeth are made of ivory and the denture has attachments for springs to keep it in place.

Then there is a battery-powered hearing aid with four microphones built in 1916 by the Hutchison Acoustic company of New York and used by Lord Knutsford. If you are used to today's miniaturised hearing aids the size of this unit will be an eye-opener! Lord Knutsford suffered acute hearing loss after an automobile accident in 1915 and used this hearing aid until his death.

The Royal London Hospital Museum is utterly fascinating; though exhibits such as the Elephant Man and Jack the Ripper displays will draw many visitors, it is the display of early medical instruments and nursing equipment that are most appealing. You'll see early medical texts, uniforms, medals, amputation saws used in the days before anaesthesia, and dental instruments that will make you positively thrilled to go to a modern dentist.

There is information on the history of nursing and the development of the NHS, as well as the growth of London's East End. There are absorbing medical documentaries - when we visited we were enthralled by an outstanding documentary on disability.

This is an outstanding museum, and well worth taking the trouble to seek out.

Getting There

The museum is located in the crypt of the Victorian church of St Philip on Newark Street. The nearest underground is Whitechapel (District Line, Hammersmith & City Line, and London Overground).

From the station exit cross Whitechapel Road, turn right, then left at New Road. Cross Stepney Way and turn left on Newark Street. You will reach St Philip's church on your left. Go down a flight of steps to an entrance below street level. The museum is free to enter and has an information desk if you have any questions.