St Giles Cripplegate is one of the very few medieval churches left in London. The first church on this site was built in 1090. Poet John Milton is buried in St Giles.

History

St Giles sits rather incongruously in the middle of the Barbican development, surrounded by modern buildings, but the church has been a part of London history for over 1000 years. The first church on this spot was built in the late Saxon period, but no trace of this early building remains; we know practically nothing about it save that it was probably built of timber with wattle and daub walls. Sometime before 1090 Alfune, the Norman Bishop of London, built a new church in stone.

The original church dedication seems to have lacked the 'Cripplegate' suffix; that was added in the Middle Ages when the church was known as St Giles without Cripplegate ('without' meaning outside). The Cripplegate referred to one of the defended gateways into the city of London.

It does not refer to lame or crippled people, as you might expect, but comes from the Saxon word 'cruplegate', meaning a tunnel or covered walkway. The tunnel or walk must have run from the city gate to the Barbican watchtower. Near the church, you can still see sections of the medieval city wall, built upon Roman foundations.

The expanding population of London outside the city walls meant that St Giles served a much larger population in the late Middle Ages. The church had to be expanded in 1394 when it gained its large Perpendicular Gothic windows. By contrast, the striking brick tower is a relatively late addition, added in 1694. The base of the tower reuses Norman stones from the 1090 church.

St Giles was damaged by fire in 1545, again in 1897, and yet again during the Blitz. It remarkably escaped the devastation of the Great Fire of London in 1666. When fire struck again in 1897 the architect charged with rebuilding the church was Godfrey Allen.

Allen was fortunate enough to find drawings made for the 1545 restoration in the records at Lambeth Palace, and was able to rebuild the church as closely as possible to its original medieval condition.

The church was hit twice in the Second World War, the second time so badly that even the cement caught fire from the heat. The chancel arcade survived, as did the tower and outer walls. Though most of the interior furnishings were lost in the blaze, several important historic features were saved. Those include the 19th century brass lectern.

The devastation of the Blitz is one reason that the interior is so spacious and filled with light. In the chancel you can se the medieval sedilia and piscina, and remains of Roman tiles are set into in the arch. At the west end is an 18th century font, and a display area on the south wall shows off a few of the church's best historic artefacts. Among these are early 17th century wine cups, a 1693 badge of office used by a Beadle, and a pepperpot from the time of George IV.

The Shakespeare Connection

On the wall is a memorial to Margaret Lucy, dated 1634. Margaret was the great-granddaughter of Sir Thomas Lucy, also buried here. William Shakespeare used Lucy as the inspiration for Justice Shallow in two of his plays, indeed, he is thought to have had to flee Stratford upon Avon for London when caught poaching Lucy's deer.

Shakespeare came to stay with his brother Edmund, who lived in Cripplegate parish, so it would not be surprising if he attended worship at St Giles. If he did, he might have received a rude shock, for the Lucy family also attended St Giles when in London. Edmund Shakespeare's 2 sons were baptised at St Giles, and according to tradition, William acted as chief witness for both ceremonies.

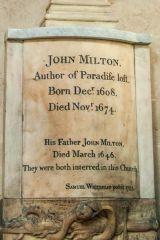

The most famous person buried at St Giles is the blind poet, John Milton. A bust to Milton stands under the organ gallery, near a memorial to writer Daniel Defoe, also a parishioner of Cripplegate. Other famous people with connections to the parish include John Bunyan, who lived in Cripplegate and is known to have attended church services here, and Oliver Cromwell, who was married here in 1620.

John Foxe, author of Foxe's Book of Martyrs, preached here, and explorer Martin Frobisher lived on nearby Beech Street. Another explorer, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, had one son baptised here and another buried in the churchyard. Playwright Ben Jonson lived in Cripplegate and 2 of his sons are buried here.

Visiting

St Giles is usually open daylight hours. I found it an absolute delight; though it is a shame that the bomb damage destroyed so many of the original interior fittings, the result is a remarkably spacious and light-filled space. The contrast between the medieval church and the modern surroundings is startling, almost jarring, but St Giles exudes a sense of history and heritage, even amidst the concrete jungle of the Barbican.

About St Giles Cripplegate

Address: Fore Street,

London,

Greater London,

England, EC2Y 8DA

Attraction Type: Historic Church

Website: St Giles Cripplegate

Location

map

OS: TQ323816

Photo Credit: David Ross and Britain Express

Nearest station: ![]() Barbican - 0.2 miles (straight line) - Zone: 1

Barbican - 0.2 miles (straight line) - Zone: 1

HERITAGE

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

Historic Time Periods:

Find other attractions tagged with:

17th century (Time Period) - 18th century (Time Period) - 19th century (Time Period) - brass (Historical Reference) - Cromwell (Person) - George IV (Person) - Medieval (Time Period) - Norman (Architecture) - Oliver Cromwell (Person) - Perpendicular (Architecture) - Restoration (Historical Reference) - Roman (Time Period) - Saxon (Time Period) - Shakespeare (Person) - Stratford-upon-Avon (Place) - William Shakespeare (Person) -

NEARBY HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS

Heritage Rated from 1- 5 (low to exceptional) on historic interest

Museum of London - 0.1 miles (Museum) ![]()

St Botolph's-without-Aldersgate Church - 0.2 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

St Anne and St Agnes Church - 0.2 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

Postman's Park - 0.2 miles (Park) ![]()

London's Roman Amphitheatre - 0.2 miles (Roman Site) ![]()

St Lawrence Jewry - 0.2 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

Guildhall Art Gallery - 0.2 miles (Museum) ![]()

St Bartholomew-the-Great - 0.3 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

Nearest Holiday Cottages to St Giles Cripplegate:

Leaves Green, Greater London

Sleeps: 6

Stay from: £857 - 3127

Culverstone Green, Kent

Sleeps: 2

Stay from: £353 - 1071

More self catering near St Giles Cripplegate