St Saviour's Church in Dartmouth is a superb medieval building that rightly features in Simon Jenkins' popular book 'England's Thousand Best Churches'. The church dates primarily to the 14th century, but the story of its origins go back almost a century earlier in time.

History

In 1286 King Edward I was visiting Dartmouth as part of his preparations for launching an invasion of France. At that time the parish church was St Clement's Townstal, which stood on top of a high hill above the River Dart.

The town, however, had shifted its focus of settlement to the foreshore. The townsfolk petitioned the king for the right to build a new parish church close to the waterfront, on account of the 'very great fatigue' caused by having to walk up the hill to attend services in St Clement's Church.

King Edward's Permission

King Edward acquiesced, and granted the townsfolk permission to build a new church, but there was one problem; he hadn't consulted the Bishop of Exeter, or the Abbot of Torre at Torquay, who appointed the priest of St Clements and who would be responsible for maintaining a new church.

The Abbot pointed out, rightly, that there weren't enough townsfolk in Dartmouth to financially support two churches, even though land for building a new church had been given by the Bacon family.

So, for the next 43 years, nothing happened, and the very idea of a new church seemed to have died. Things changed in 1329 when the priest of St Clement's Townstal committed suicide. This was considered a grave sin by the Catholic Church, and the Abbot of Torre decided to punish the parish by banning all church services including christenings, burials and marriages. The ban lasted two years and must have caused enormous difficulty for the parishioners of Dartmouth.

The Friar's Chapel

Then the situation got even more tangled. William Bacon, the son and heir of the Bacon who originally gave land to build a new church, decided to grant the very same parcel of land to a pair of friars of the Hermits of St Augustine order. The friars immediately started to build a church on the site.

The Abbot of Torre was livid. He was concerned that the new church would compete for donations with the existing parish church of St Clement. He took the extraordinary step of excommunicating William Bacon, the most severe punishment he could administer. He also claimed that the friars were posing as priests and ordered them to stop building their church.

He relented - slightly - in 1334 and allowed the friars to use their chapel but not to hear confession or celebrate mass. He also removed the sentence of excommunication on William Bacon.

The legal status of the Augustinian chapel was disputed for the next decade, and in 1344 the friars were ordered to tear it down. The friars appealed for help from the Pope.

Then events took a truly bizarre turn.

The Bishop of Damascus appears

A stranger appeared, claiming to be the Bishop of Damascus, who said he had been sent by the Pope to consecrate the chapel. This he did, after which he confirmed several children and removed the ban of excommunication from several townsfolk. The truth emerged; the stranger was, in fact, a friar from Cambridge, who claimed to have a dispensation from the Pope to consecrate places of worship.

The 'consecration' was not officially recognised, and the legal battles over the friar's chapel continued. Finally, in 1372 the Abbot of Torre and the Bishop of Exeter relented and gave the townsfolk of Dartmouth permission to build a new parish church. It had taken 86 years from Edward I's original grant of permission.

The townsfolk of Dartmouth built the new church themselves and dedicated it to the Holy Trinity and St Mary. The church was consecrated by Bishop Brantingham of Exeter in October 1372. At some point prior to 1430 it was rededicated as St Saviour's.

Historical Highlights

The Medieval Door

You don't even have to enter the church to see one of St Saviour's most remarkable historical features. The south door has been carbon-dated to 1361 (it bears the date 1631 but that is merely the year it was repaired). The door is decorated with an extraordinary example of medieval ironwork. You can see a Biblical 'Tree of Life' and a pair of leopards, a popular symbol in Plantagenet times.

The Hawley Brass

Protected by a carpet in the chancel is a superb memorial brass commemorating John Hawley and his two wives. Hawley (d 1408) was an infamous privateer and 14-time Mayor of Dartmouth. He was granted a license by the Crown to sail the seas in search of bounty, which he shared with the king.

At least, that was the idea; it seems that Hawley, who owned 30 ships, sometimes forgot the 'share' part of the bargain. He was hauled before the courts on a charge of piracy but escaped punishment. It was Hawley that helped build the fort that later became Dartmouth Castle.

Not all Hawley's escapades took place on the high seas. He famously helped repel a French invasion force of 2,000 knights and men at arms who landed at Slapton Sands. Hawley led a band of local men, many of them farm labourers, and fought off the French. The labourers were aided by their wives who were said to be experts with slings.

Hawley also granted money to build the chancel that is now his final resting place. Hawley's brass is flanked by figures of Joanna, his first wife (d 1394) and Alicia (d 1404). The result is the largest brass in Devon and one of the finest in England.

As mentioned above, the brass is usually covered by a carpet. We were fortunate enough to visit when a volunteer steward was showing the brass to some other visitors. She asked if we would like to see it, too - so of course, we said yes.

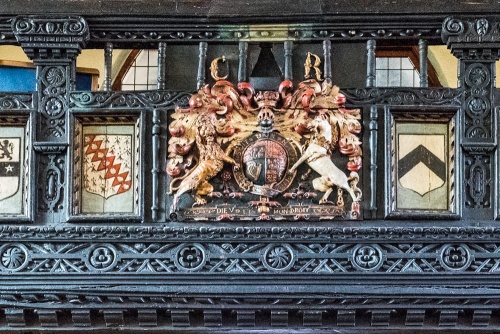

The west end of the church is taken up by a large gallery decorated with coats of arms. The fourth from the right is that of John Hawley II. The fifth from the left belongs to John Hawkins and the sixth is that of another naval hero, Sir Francis Drake. In the centre of the gallery is a royal coat of arms to Charles II. The gallery is said to be made with timbers from a Spanish ship captured in the Armada invasion of 1588, though the gallery itself was built in 1633.

Another historical highlight linked to the Spanish Armada is a 16th-century Armada Chest, used by a naval officer at the time of the Armada. The chest has an intricate iron locking system and is so heavy that it would have taken several men to carry.

Under the gallery is the very plainly carved octagonal font, probably dating to the 14th century.

St Nicholas Chapel boasts a piscina from around 1440.

Separating the chancel from the nave is an outstanding late-medieval oak screen, crafted around 1480. This is one of around 180 such screens in Devon to have survived the Reformation. Instead of being destroyed it was dismantled and put into storage. It was only reinstalled in 1904.

The base of the screen is painted with figures of saints while the ornately carved tracery depicts grapes, wheat, and intertwined ropes, illustrating the maritime history of Dartmouth. Look amid the foliage for the face of a Green Man.

The pulpit is also of 15th-century construction, and is a medieval rarity; a painted stone pulpit. A slender octagonal stem widens to form an octagonal drum with timber doors. The drum is decorated with later initial of King Charles I.

The oldest wall monument is to Nicholas Hayman (d 1606), while on the south side of the church is a marble memorial in neo-classical style to Walter Jago (d 1733)

Most of the original stained glass was blown out by bombs in 1943, but fragments of heraldic 17th-century glass survive including an oval plaque commemorating q 1634 gift of money for window glass by Thomas Pagge.

Visiting

St Saviour's is a delight, a superb medieval building full of historical interest. The church stands on Anzac Street, a stone's throw from Dartmouth Museum and the harbour. The church is usually open daylight hours and was open when we visited. There are several pay and display parking areas along the waterfront but we strongly recommend using Dartmouth's park and ride system, especially during the summer months when the waterfront area can be extremely crowded.

About Dartmouth, St Saviour's Church

Address: Anzac Street,

Dartmouth,

Devon,

England, TQ6 9DL

Attraction Type: Historic Church

Location: On Anzac Street, off Smith Street and Newcomen Road

Location

map

OS: SX877513

Photo Credit: David Ross and Britain Express

HERITAGE

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

Find other attractions tagged with:

NEARBY HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS

Heritage Rated from 1- 5 (low to exceptional) on historic interest

Dartmouth Museum - 0.1 miles (Museum) ![]()

Bayard's Cove Fort - 0.2 miles (Historic Building) ![]()

Dartmouth Castle - 0.7 miles (Castle) ![]()

Gallants Bower Fort - 0.8 miles (Historic Building) ![]()

Dartmouth, St Petrox Church - 0.8 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

Coleton Fishacre House and Garden - 1.9 miles (Historic House) ![]()

Greenway - 2.3 miles (Historic House) ![]()

Stoke Gabriel Church - 4 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

Nearest Holiday Cottages to Dartmouth, St Saviour's Church:

More self catering near Dartmouth, St Saviour's Church