Florence Nightingale's influence on the history of nursing and medieval treatment for soldiers cannot be overstated. Though she is remembered first and foremost for her role during the Crimean War as 'The Lady with the Lamp', it was actually her efforts after the war ended that helped change our attitude towards the treatment of wounded soldiers and hospital treatment in general.

After the Crimean War ended, Nightingale wrote a meticulous report, using statistics that proved beyond doubt that more British soldiers had died from disease than from wounds suffered in combat. Her report led to a Royal Commission, and reforms in the way soldiers were treated. Those reforms eventually led the way to our modern concept of nursing care.

In 1860 Nightingale founded the Nightingale Training School of Nursing here at St Thomas Hospital in London.

Among the objects on display are many of Nightingale's personal belongings, including the slate she used as a child and the Turkish lantern she used during the Crimean War. Victorian paintings depicting the 'Lady with the Lamp' usually showed her with an oil lamp or some form of a romanticised medieval-style lamp, but in reality, she used the local Turkish lantern. The lantern on display is one of those used during her time in the Crimea and almost certainly one that she would have carried on her nightly rounds.

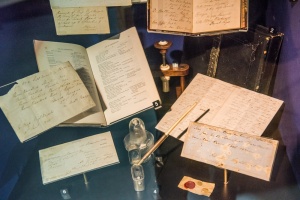

hand-written letters

The museum also has over 1,000 handwritten letters, though only 100 or so are on display. Most of the objects in the collection were acquired by Dame Alicia Lloyd-Still who served as Matron of St Thomas’ Hospital from 1913-1937. The collection was first shown to the public in 1954 to mark the centenary of the Crimean War.

The range of personal effects is amazing, and include some very unusual objects, such as Florence's stuffed owl, Athena, that used to travel everywhere with her in her pocket. She was very fond of Athena, though the owl was known to be very bad-tempered.

Florence found Athena as an owlet while visiting the Acropolis in Athens, and named it after the Greek goddess of wisdom. Athena died while Florence was on her way to Turkey during the Crimean War. Florence was quite upset by the bird's death and wrote, 'Poor little beastie, it was odd how much I loved you'.

Other personal objects include a small gold and gemstone cross that Florence wore on a chain, and the beautifully made medicine chest that Florence took to the Crimean battlefield. A fascinating display looks at three of Florence's rejected suitors. Her refusal to marry any of the men caused a great deal of family friction.

The museum is arranged into several distinct parts. The first part deals with Florence Nightingale's childhood and upbringing and includes several sketches of Florence by her sister Parthenope. Other sections deal with Florence's training in nursing, her journey to the Crimea, and her experiences battling military and political bureaucracy in her efforts to reform medical practice both in the field and back in Britain. The final section deals with Florence Nightingale's lasting influence on nursing and health-care over time.

- the most famous image of

Florence Nightingale,

but one she refused to pose for.

Also part of the museum is a series of WWI oil paintings by French artist Victor Tardieu, showing life in a field hospital. Another fascinating portrait on show is a copy of the 1856 painting, 'The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari'.

This painting, by Jerry Barrett, became the most popular image of Nightingale during her lifetime. However, Florence refused to sit for the group portrait; she consistently tried to downplay her own role and was concerned lest the popular focus on her risked antagonising the military medical establishment that she had to work with.

The museum has a regular programme of exhibits. Some current and forthcoming displays include 'Notes and Swearies: Obscene Language in Soldier's Speech', and 'Edith Cavell: Nurse and Patriot'.

Visiting

When I visited I thought the museum was rather poorly signed, like a bit of an afterthought, tucked away on one side of the entrance to St Thomas Hospital. Having said that, it is fairly easy to get to, just over Westminster Bridge from the Houses of Parliament, and just along the river from the London Eye.

It is amazing to think just how much influence this one courageous woman had, overcoming entrenched beliefs and stifling bureaucracy to create a more humane and sensible way of caring for ill people - not just soldiers.