The little that remains of the fenlands of East Anglia provides only a glimpse of what this desolate area of marshland was like for centuries. Since the age of the Romans, the fens were a remote and inaccessible region composed of tufts of solid ground rising above shallow water, reed-beds, pools and mires.

The rivers of the Welland, Witham, Glen, Nene, Cam, Great Ouse, and Little Ouse made of the fens a vast inland waterway navigable only in shallow-bottomed boats, the forerunners of today's punts.

The fens were rich in sea life; in 1125 the monk William of Malmesbury declared, "Here is such a quantity of fish as to cause astonishment in strangers while the natives laugh at their surprise".

The most common fish in the fens were eels, which were not only caught and eaten but used as currency! Rents, debts, and tithes were often settled by payment in eels. In addition, the fens have always supported a vast variety of birdlife.

Fen dwellers harvested reeds, peat, and rushes for sale, and so essential were these natural materials to the economy of the area in medieval times that their harvest was carefully regulated by local landowners.

The Romans schemed to drain the fens, but they got no further than building the Car Dyke to keep the sea at bay.

After the departure of the Romans in the fifth century, the Anglo-Saxons founded a series of isolated monasteries on islands in the fens. Ely is one such island, and its name is a reminder of the area's rich sea life; Ely translates as "island of eels".

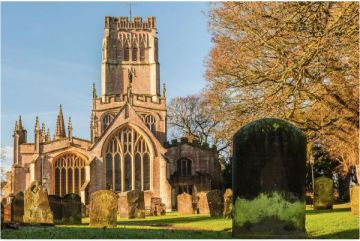

Crowland Abbey is a good example of an isolated Saxon monastery site. It was established by St Guthlac in the late 8th century, but even in the 13th century Mathew Paris could proclaim that Crowland was, "a place of horror and solitude".

The isolation of the fens proved an invaluable aid to Hereward the Wake in his revolt against the Normans. The native British rebel held out against the might of William the Conqueror by using the treacherous marshes as a barrier.

DRAINING THE FENS

Elizabeth I was interested in draining the fens to provide for agriculture, but it was left to the Duke of Bedford in the 17th century to take matters in hand.

In 1626 the Duke gathered support from a group of investors and called in Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden to drain Hatfield Chase. Vermuyden devised a series of ditches ('cuts') and dykes that bit by bit reclaimed the rich peat soil beneath the waters.

The scheme was violently opposed by the natives of the fens, both because Vermuyden employed Dutch workers, and because of the changes the draining would have on their traditional hunting and fishing rights. They attacked the workmen, and it was only after an agreement was reached to compensate the fen-dwellers and employ English workers that the project could proceed.

Vermuyden devised a scheme to drain the Great Fen, in return for which he was promised 96,000 acres for himself. His work was undone in 1642 when the Parliamentary army broke his dykes in an effort to flood the land and stop a Royalist army from advancing. In 1649 Vermuyden went back to work, this time with the labour provided by Scottish and Dutch prisoners of war.

The Great Fen reclamation drained over 40,000 acres of land but had the unexpected consequence of causing the neighbouring farmland to sink. This happened when the peat topsoil dried out and settled. In some cases land sunk up to 20 feet below the level of the cuts.

Today the old fens survive in isolated pockets. One such is Wicken Fen, a protected environment that was the very first National Nature Reserve in England.