Coram was moved by the plight of London's poor children, many of whom were left to fend for themselves when their parents died or were simply unable to care for them. His new Hospital was intended to educate and care for the children of reputable single women whose partners had left them to fend for themselves. The Hospital rules were very particular; each child's mother was vetted and had to show that she had previously had a good reputation before having the child.

The Hospital was not an orphanage, and would not accept children whose father's were known and alive, because the father could, in theory, be prevailed upon to accept responsibility for looking after the child. Each mother gave the child a unique token, such as a coin or bead, which was sealed with the family records, to be used as identification in case relatives wished to reclaim the child at some future date. Each child was given a new name, and all ties to their existing families were cut off. Some of the children were given names like Walter Raleigh or William Shakespeare.

The Foundling Hospital Collection

In 1739 Thomas Coram established a charitable hospital to care for the 1000s of children who were abandoned each year in the capital. The Hospital was an essential part of the London scene until 1954 and lives on today through the charity Coram. The museum collection contains a multitude of memorabilia covering two centuries of the Hospital in London, with prints, sculpture, paintings, manuscripts, clocks, and furniture with ties to the Hospital.

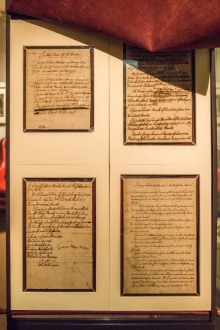

The museum also tells the very personal tales of the 25,000 children who were aided by the Hospital over that time, The Foundling Hospital maintained precise records, and some of those records are on permanent display, while the full archive is preserved in the London Metropolitan Archives. The museum was created in 1998 to look after the Foundling Hospital Collection, and it is housed in a purpose built building that once served as the Hospital's London headquarters.

The Gerald Coke Handel Collection

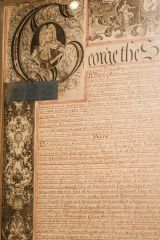

This is one of the world's best collections relating to Handel's life and work, includes original scores, printed music and books, coins, manuscripts, artwork and a multitude of other Handel ephemera that defy categorisation! One item that caught my eye was a pitch pipe donated by Handel in 1756 when he presented the Chapel organ to the Hospital. One of the prize documents on view is Handel's will. In addition to the Collection, the museum also holds the research archives of Handel House Museum.

Handel served as an original Governor of the Foundling Hospital. In 1749 he offered a benefit concert to raise money for a Hospital chapel. He composed an anthem called 'Blessed are they that considereth the poor', afterwards known as the Foundling Hospital Hymn. The fundraiser was so successful that the governors asked Handel to return the following year. This he did, and each year until his death in 1759 he put on The Messiah in aid of the Hospital.

William Hogarth

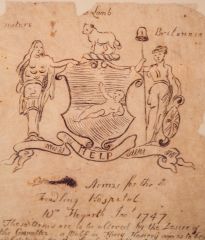

The museum houses a fascinating display on engraver William Hogarth, a staunch supporter of Coram's aims. One of Hogarth's best-known engravings is Gin Lane, showing the squalor and destitution of London's lower classes. He was a man moved by the plight of the poor and determined to improve their lot. You can see the sketch Hogarth made for the Foundling Hospital coat of arms, but my favourite Hogarth piece is a large painting entitled The March of the Guards to Finchley, 1750.

by William Hogarth

When the final date to pre-order engravings was reached there were still 167 unsold. Hogarth donated the unsold lottery tickets to the Foundling Hospital, and with the increased odds it is not surprising that the Hospital won the lottery. The painting now occupies a place on the wall in an ornately gilded frame.

Visiting

The Foundling Museum is a treasure; one of London's finest small museums and a delight to visit. It is really a museum in three parts; the first part tells the poignant story of the Foundlings and how the hospital operated. You can see the uniforms the children wore, and hear recordings of relatively recent foundlings telling their stories. The most touching displays are tokens left with the children by their mothers, who might reasonably expect to never see their child again.

Beyond the Foundling displays are a series of ornate 18th-century rooms with fine art on the walls, and the Hospital's collection of fine silver. There are more period rooms on the first floor, with a display on the life of William Hogarth, while the Handel Collection occupies the top floor of the museum. Take your time, there is a lot to see and enjoy. The Foundling Museum offers a wonderful visiting experience; a glimpse into a troubling aspect of London's history, and the men and women who were determined to change the lives of poor children for the better.

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.