Depending on which version of its long history you adhere to, St Pancras Old Church may be the oldest place of Christian worship in Britain, with its roots going back to AD 313. That may be a stretch, but there are Roman bricks and tiles incorporated in the church's north wall, and the dedication to St Pancras does suggest an ancient origin.

History

There was almost certainly a church here before the Norman Conquest of 1066. There is no church mentioned in the Domesday Book, but the name is used to refer to property held by the canons of St Paul's Cathedral, so it seems clear that there was a church here by that time. The church possessed a 6th century stone altar said to have been used by St Augustine.

The first documentary record comes from a pair of deeds dated between 1160-1180 in which Ralph de Kentewode confirms grants of land to the church of St Pancras. In 1181 it was given to the Chapter of St Pauls and the parish tithes were used to support a hospital within the Cathedral.

In the reign of Edward VI (c. 1549) the vicar was a reformer named John Bedstow, who had the peculiar habit of preaching from the branches of a tall tree in the churchyard and saying Mass from a tomb inside the church rather than from the high altar. In the late Elizabethan period it was described as being 'all alone, as utterly forsaken, old and weather-beaten', and in the 17th century it was said to be 'in the fields remote from any house' - something which is hard to imagine today!

By the Civil War, it was utterly deserted, so it comes as no surprise that in 1642 Parliament instructed that the 'deserted church of Pancras' should be used as a lodging for 50 army troopers. It was around this time that the 6th-century altar stone went missing.

The church was rarely used during the 18th century except for burials. When a new church was built in Euston Road in 1822 the Old Church lost its parochial status and became a chapel of ease.

By 1848 the medieval building, which had remained scarcely altered since the 12th century, was in dire condition. Help was at hand; as the City of London expanded in the middle of the 19th century the isolated area north of the old city walls was swallowed up by new development and the decrepit church was no longer isolated at all, but surrounded by the growing city, and the growing population needed churches.

The church was completely restored by the architect AD Gough, who swept away most of the medieval structure, tore down the tower and removed the south porch. When workmen dug under the tower foundations they discovered the 6th-century altar stone, along with the medieval church plate. Presumably, these valuables had been hidden to prevent damage during the time the church was taken over by the Parliamentarian soldiers.

The new building was designed in 12th-century style, with completely new doorways and windows. Gough did retain a section of the north wall, which has been left exposed on the interior so that you can see the 12th-century stonework, which incorporates Roman bricks and pieces of tile.

Set into this wall is an Easter Sepulchre, moved here from the sanctuary. Set into the back of the Easter Sepulchre is the indent of a memorial brass made around 1530 and said to commemorate a member of the Grey family. The indent shows a woman and her 2 husbands, with her 13 children from both marriages.

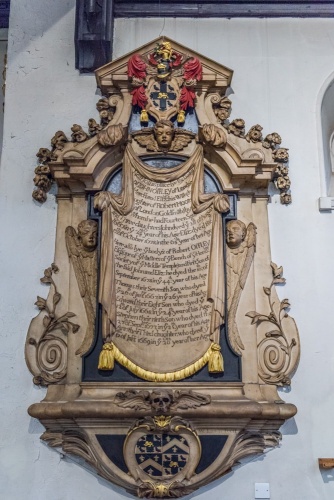

This is the oldest, though perhaps the least impressive of the memorials inside the church. There are at least 4 excellent 17th-century memorials on the chancel walls, including a striking monument to William (d 1637) and Mary Platt nee Hungerford (d 1687). Those dates are correct; Mary outlived her husband by 50 years.

The monument shows busts of the couple, each within a separate rounded niche and surrounded by 38 heraldic plaques detailing every family connection of the Platt and Hungerford families. The memorial was originally installed at the old School Chapel at Highgate and was moved here in 1833.

Nearby on the south wall of the nave is a monument to Samuel and Christina Cowper (died 1672 and 1693 respectively). This white marble monument is in the form of a cartouche supported by a pair of cherubs. Where you might expect to see a crest is instead a gilded artist's palette with brushes, a reminder that Samuel Cowper gained fame as a painter of miniatures. His most famous work was a portrait of Oliver Cromwell.

Earlier by some 50 years is a memorial to Daniel and Katherine Clarke (d. 1626 and 1613 respectively). Daniel served as a royal cook for King James I and VI. Katherine was the daughter of John Izod, a 'Gentleman Usher of the Queen's Majesty's Prlvie Chamber'.

Churchyard

In the days before London expanded to envelope St Pancras churchyard, when the church was a lonely, isolated spot, it was a target for grave robbers, who dug up freshly interred bodies and sold them to doctors for medieval dissection. The church gained a sinister reputation, a reputation known to Charles Dickens, who used the burial ground in A Tale of Two Cities as the site where Jerry Cruncher brings his young son to do a spot of 'fishing' (digging up recently buried bodies).

Outside the churchyard is St Pancras Garden, formed from what is left of the original graveyard and opened as a public park in 1877.

The Hardy Tree

In 1864 the Midland Railway launched an ambitious scheme to connect London to the north of England by rail. The scheme would see railway lines from Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds and Bradford converge at a new rail station at St Pancras. In order to make space for the new railway lines, the company took part of the St Pancras Old Church graveyard.

This meant that the existing burials had to be moved. It might have been possible to route the lines to avoid the graveyard, but that would also mean that passengers would make their arrival in London to be faced with the sight of a row upon row of gravestones.

The Bishop of London, in whose diocese the graveyard fell, called on architect Sir Arthur Blomfield to come up with a solution. Blomfield assigned the task to his assistant, a young architect named Thomas Hardy.

Hardy, of course, is better known today as the author of such timeless novels as Tess of the D'Urbervilles and Far from the Madding Crowd but in 1865 he was simply a young, inexperienced architect. Hardy was given the unpleasant task of taking down thousands of gravestones and memorials, disinterring the bodies beneath, and reburying them in a mass grave.

A large number of the old gravestones were gathered together, crammed side by side, with an ash tree planted at the centre and clipped hedges around the outside of the site. The tree's gnarled roots now grow over, around, and through the gravestones as an organic, ever-changing memorial. This is the 'Hardy Tree', though whether Hardy actually had any say in planting the tree is debatable.

Mary Wollstonecraft

A stone's throw from the Hardy Tree is the gravestone of Mary Wollstonecraft, the writer, philosopher, and controversial advocate of women's rights. Wollstonecraft's book 'A Vindication of the Rights of Woman' (1792) was one of the earliest and most important works of feminist philosophy. She died of complications from childbirth in 1797.

Her husband William Godwin was buried beside her in 1836 as was his second wife Mary Jane Godwin. In 1851 her grandson Percy Shelley had her remains moved to Bournemouth for reburial. Shelley was the son of Mary's daughter, Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, and the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. So, though Wollstonecraft's gravestone survives, there is no one buried under it.

Sir John Soane

Set off from the rest of the Garden by an iron railing is the tomb of the architect Sir John Soane, whose most famous design was that of the original Bank of England building on Threadneedle Street. Soane designed his own tomb, with a low stone balustrade surrounding a peculiar open structure like a stone gazebo protecting an inner neo-classical monument. The outer structure is said to be the inspiration for the ubiquitous K9 telephone box design.

The designer was Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, who was a trustee of the Soane Museum on Lincoln's Inn Fields and would have been very familiar with Soane's work. Gilbert Scott's grandfather Sir George Gilbert Scott designed the original St Pancras Hotel, so it is quite possible that Sir Giles visited the original tomb.

John Flaxman

Just a few steps from the Soane memorial is the grave of the popular funerary sculptor John Flaxman (1755-1826). Flaxman was a self-educated artist who worked as a modeller for Josiah Wedgwood pottery company before gaining fame as a sculptor of memorials. His work was known for its beautiful simplicity and depiction of domestic sentimentality. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1800 and in 1810 the academy created a special 'Professor of Sculpture' post for him.

Burdett Coutts Memorial Sundial

The most impressive, eye-catching monument in the Garden is a huge sundial in the form of a stepped pyramid, erected in 1879 by Baroness Burdett Coutts as a memorial to those whose graves were disturbed by the railway line. Among those whose names appear on the memorial are the architect Sir John Soane, sculptor John Flaxman, Sir John Gurni and James Leon.

The memorial was designed by George Highton and is topped by a pinnacle of Portland limestone supporting a sundial. Four marble panels bear Biblical inscriptions and mosaic panels are set into the steps. The monument is surrounded by railings, on which is a plaque commemorating the composer Johann Christian Bach, who was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave in the churchyard.

One of the names listed on the monument is the Chevalier D'Eon (Charles-Genevieve-Louis-Auguste-Andre-Timothee d'Eon de Beaumont), a French diplomat, soldier, and spy who died in 1810. D'Eon was androgynous, and successfully infiltrated the court of Empress Elizabeth of Russia as a woman, acting as one of King Louis XV's network of spies known as the 'Secret du Roi' (the King's Secret). S/he spent the last 33 years of his/her life as a woman before dying in poverty. The Chevalier's grave was one of those lost when the graveyard was moved to make room for the railway to St Pancras station.

William Blake

Was St Pancras Old Church the inspiration for William Blake's poem 'And did those feet in ancient time' (often wrongly called 'Jerusalem' after Blake's poem was set to music in a hymn of that name by Sir Hubert Parry)? According to one tale, Blake knew of a legend that said Jesus had visited London with his uncle, a metal trader. A spiritual site was said to exist at the highest navigable point on the River Fleet, where St Pancras Old Church now stands, and Jesus was said to have visited the site.

Blake drew on the legend to create his famous poem. He certainly would have been acquainted with the church, for he had acted as an illustrator for Mary Wollstonecraft on several of her books, and he admired her work.

The Beatles Connection

Beatles fanatics will know the Old Church as the setting for a photo shoot for the band's Mad Day Out. John, Paul, George and Ringo used the courtyard and the church grounds for their shoot, with informal photos taken in the Gardens and formal shots incorporating the extravagantly carved west doorway arches. The musical legacy has continued in more recent years as the church has become a popular musical performance venue for the likes of Sinead O'Connor and Brian Eno.

Getting There

St Pancras Old Church is a delight, a slice of history in the heart of modern London. The church is easy to reach on foot from Kings Cross/St Pancras station. From the station exit turn west on Euston Road (A501), then right on Midland Road. Follow Midland Road north until it becomes Pancras Road. You will find the Old Church and Gardens on your right, through a set of elaborate wrought-iron gates. The church is usually open to visitors and was open when we visited.

About St Pancras Old Church

Address: Pancras Road,

London,

Greater London,

England, NW1 1UL

Attraction Type: Historic Church

Location: On Pancras Road, north of St Pancras rail station

Website: St Pancras Old Church

Location

map

OS: TQ297834

Photo Credit: David Ross and Britain Express

Nearest station: ![]() Mornington Crescent - 0.4 miles (straight line) - Zone: 2

Mornington Crescent - 0.4 miles (straight line) - Zone: 2

HERITAGE

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

Find other attractions tagged with:

NEARBY HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS

Heritage Rated from 1- 5 (low to exceptional) on historic interest

British Library - 0.4 miles (Museum) ![]()

London Canal Museum - 0.4 miles (Museum) ![]()

Jewish Museum - 0.6 miles (Museum) ![]()

Foundling Museum - 0.8 miles (Museum) ![]()

Grant Museum of Zoology - 0.8 miles (Museum) ![]()

St Luke, Oseney Crescent - 0.9 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

Fitzroy House - 0.9 miles (Historic House) ![]()

Charles Dickens Museum - 1 miles (Museum) ![]()

Nearest Holiday Cottages to St Pancras Old Church:

Leaves Green, Greater London

Sleeps: 6

Stay from: £857 - 3127

Culverstone Green, Kent

Sleeps: 2

Stay from: £353 - 1071

More self catering near St Pancras Old Church