Illustrated Dictionary of British Churches - Effigy Definition

History and Architecture

- Aisle

- Altar

- Ambulatory

- Angel Roof

- Apophyge

- Apse

- Arcade

- Arch

- Archivolt

- Base

- Battlement

- Bay

- Belfry

- Bell Tower

- Bellcote

- Bench End

- Board Bell Turret

- Body

- Boss

- Box pew

- Bracket

- Broach Spire

- Buttress

- Canopy

- Capital

- Cartouche

- Chancel

- Chancel Arch

- Chancel Screen

- Chantry

- Chapel

- Chapter House

- Choir

- Clerestory

- Cloister

- Communion Rail

- Compound Column

- Consecration Cross

- Corbel Head

- Crossing

- Crypt

- Early English

- Easter Sepulchre

- Effigy

- Fan Vaulting

- Font

- Font cover

- Funerary Helm

- Gallery

- Gargoyle

- Gothic

- Green Man

- Grotesque

- Hatchment

- Herringbone

- Hogback Tomb

- Holy Water Stoup

- Hunky Punk

- Jesse Window

- Kempe Window

- Lady Chapel

- Lancet

- Lectern

- Lierne

- Lych Gate

- Misericord

- Monumental Brass

- Mullion

- Nave

- Ogee

- Organ

- Parclose Screen

- Parish Chest

- Pendant

- Perpendicular Gothic

- Pew

- Pinnacle

- Piscina

- Poor Box

- Poppy Head

- Porch

- Priest's Door

- Pulpit

- Purbeck Marble

- Quire

- Rebus

- Reliquary

- Reredos

- Retable

- Romanesque

- Rood

- Rood Loft

- Rood screen

- Rood Stair

- Rose Window

- Round Tower

- Sanctuary

- Sanctuary Knocker

- Saxon Period

- Scratch Dial

- Sedilia

- Spire

- Statue Niche

- Stoup

- Tomb Recess

- Tracery

- Transept

- Triforium

- Tympanum

- Undercroft

- Vaulting

- Victorian Gothic

- Wall Monument

- Wall Painting

- Wheel Window

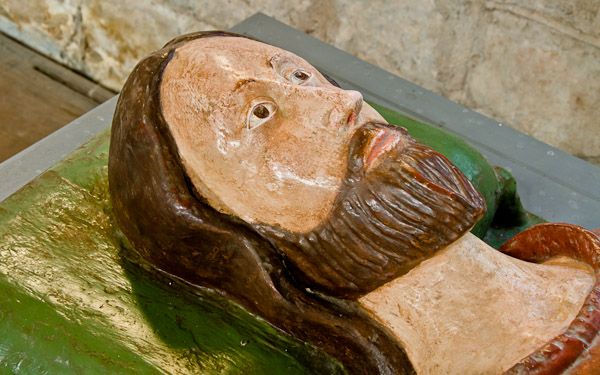

Effigy

At its most basic, an effigy is a likeness, usually of a person, usually life sized, and usually of stone. That's a lot of 'usually' for one definition! Effigies are comonly found on tombs, and most frequently as a life sized sculpture on top of a slab, or table. In the medieval period many effigies were made of wood, carved and colourfully painted. Very few of these wooden effigies have survived, with some notable exceptions at Much Marcle, Herefordshire, and Little Horkesley, Essex.

Materials

Much more common are stone effigies. These date to the 13th century or even earlier. Few of these earlier effigies have any traces of paint left on them, and most are very worn. During the medieval period effigies became very common on tombs. They were rarely intended to be an actual physical portrait of a person, and might have been sculpted many years or even decades after the subject died. A very wide variety of stone was used to sculpt effigies, with some of the more fabulous tombs using marble or alabaster.

Effigies became extremely common during the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods, and took many forms. One of the most common forms is a husband and wife lying prone, side by side, on a slab atop a rectangular base. Also common were wall monuments, with effigies carved lying on their side, beneath a decorated canopy. Sometimes generations of a family are shone with effigies stacked vertically, one generation above the next.

One of the most fascinating features of studying effigies is that the costumes worn by the carved figures show in wonderful detail the clothing in fashion at particular periods in history. Early effigies of knights give us a wonderful illustration of the armour used at the time, and later tomb effigies show in great detail the costumes worn by men and women.

One last point of interest is that you will often see effigies of 13th and 14th century knights with their lower legs crossed. This was thought for many years to indicate that the knight had been on the Crusades. This theory has now been discounted by historians, and the general consensus is that depicting knights with crossed legs was simply a stylistic convention.